Imagine an Earth-sized planet that’s not at all Earth-like. Half this world is locked in permanent daytime, the other half in permanent night, and it’s carpeted with active volcanoes. Astronomers have discovered that planet.

The planet, named LP 791-18d, orbits a small red dwarf star about 90 light years away. Volcanic activity makes the discovery particularly notable for astronomers because volcanism facilitates interaction between a world’s interior and its exterior.

LP 791-18 d is an Earth-size world about 90 light-years away. The gravitational tug from a more massive planet in the system, shown as a blue disk in the background, may result in internal heating and volcanic eruptions – as much as Jupiter’s moon Io, the most geologically active body in the solar system. Image credit: NASA’s Goddard Space Flight Center/Chris Smith/KRBwyle

“Why is volcanism important? It is the major source contributing to a planetary atmosphere, and with an atmosphere you could have surface liquid water — a requirement for sustaining life as we know it,” said UC Riverside astrophysicist Stephen Kane.

Astronomers already knew about two other worlds in this star system, LP 791-18b and c. The outer planet, c, is about 2.5 times Earth’s size, and nearly nine times its mass.

During each orbit around the star, planets c and d pass very close. As they do, c’s massive size produces a gravitational tug that makes planet d’s orbit more elliptical, rather than perfectly circular. These deformations to the orbit create friction that heats the planet’s interior, producing volcanic activity at the surface.

Researchers found the planet using data from NASA’s Transiting Exoplanet Survey Satellite, TESS, and the retired Spitzer Space Telescope. Kane was part of the team that did the original TESS observations, and he co-authored a paper about the newly discovered planet published in the scientific journal Nature.

Another key feature of the planet, as described in the paper, is the fact that it does not rotate.

“LP 791-18d is tidally locked, which means the same side constantly faces its star,” said Björn Benneke, corresponding co-author of the paper and astronomy professor at the Trottier Institute for Research on Exoplanets, based at the University of Montreal.

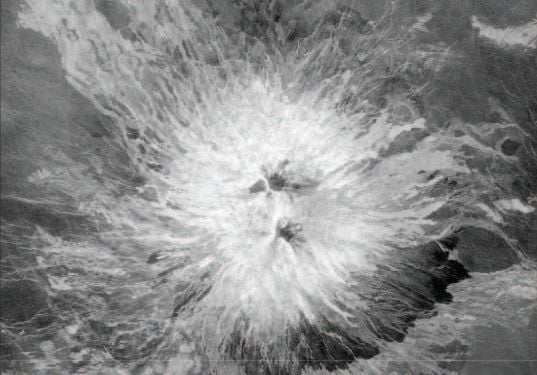

Sapas Mons, a large volcano on Venus, is about 400 km in diameter. It was imaged by the Magellan spacecraft, with a light source coming from the left side of the image. Image courtesy of JGR Planets

“The day side would probably be too hot for liquid water to exist on the surface. But the amount of volcanic activity we suspect occurs all over the planet could sustain an atmosphere, which may allow water to condense on the night side,” Benneke said.

Though the presence of so many constantly erupting volcanoes would likely make the planet uninhabitable, their presence offers new information about evolution.

“A big question in astrobiology, the field that broadly studies the origins of life on Earth and beyond, is if tectonic or volcanic activity is necessary for life,” said Jessie Christiansen, paper co-author and California Institute of Technology research scientist.

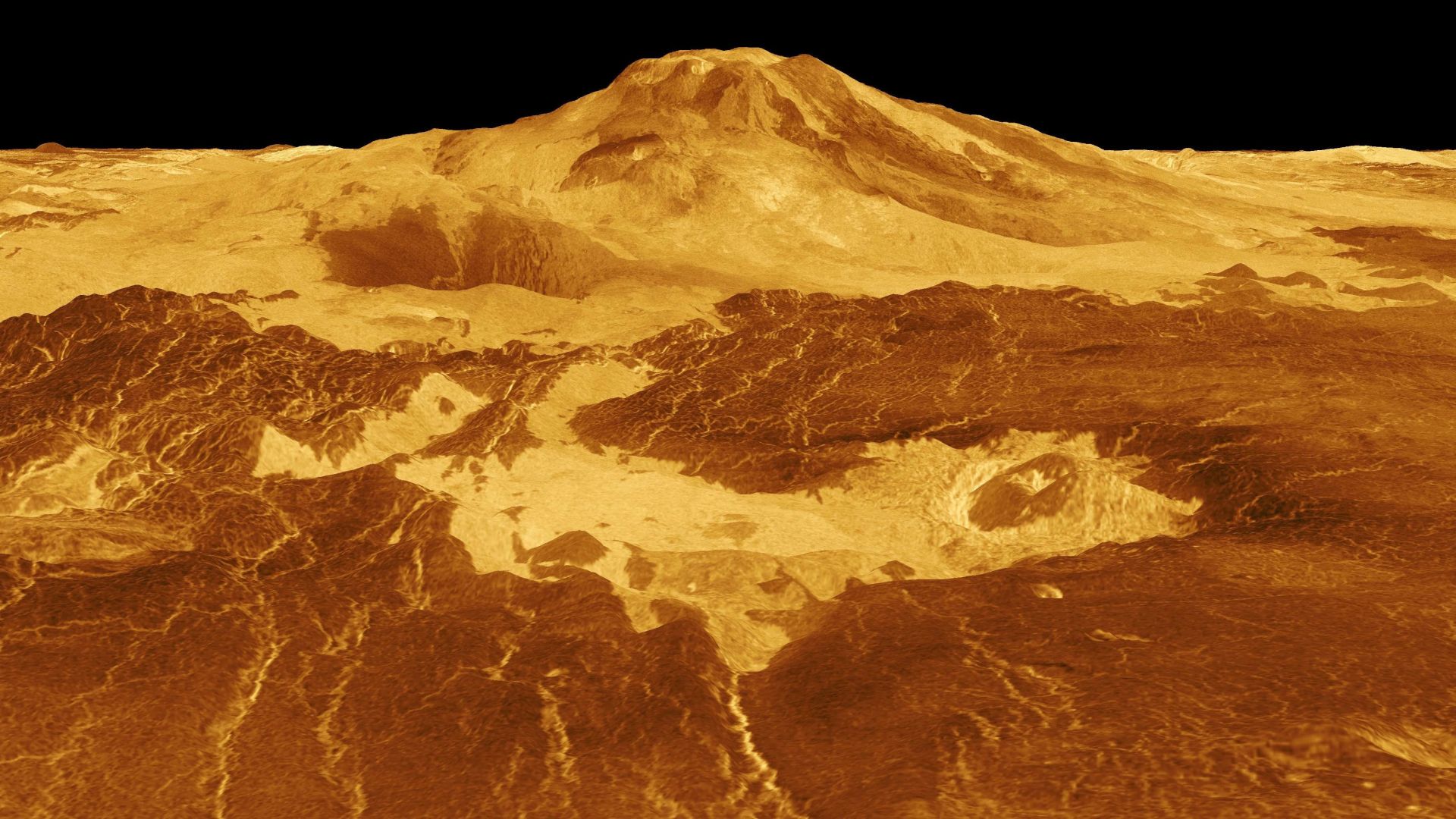

Scientists have seen direct evidence of active volcanism on Earth’s twin, Venus. This 3D model of Venus’ surface shows the summit of Maat Mons, the volcano exhibiting signs of activity. Image credit: NASA/JPL-Caltech

“In addition to potentially providing an atmosphere, these processes could churn up materials that would otherwise sink down and get trapped in the crust, including those we think are important for life, like carbon,” Christiansen said.

The recent discovery of active volcanoes on Venus also shows that planets of Earth’s size can continue adding to their atmospheres, with or without plate tectonics.

The main constituents of volcanic emissions are carbon dioxide and water vapor, greenhouse gases that can help keep a planet warm. “On Venus, volcanic carbon dioxide stayed in the atmosphere, pushing the planet into a runaway greenhouse state,” Kane said.

“Today, surface temperatures on Venus are more than 850 degrees Fahrenheit — as hot as a wood-fired pizza oven — and odds of life there are slim. But it may not always have been that way,” he said.

“Volcanoes might be a big piece of the puzzle about what actually happened on Venus. Planets like LP 791-18d can shed important insights into how volcanoes shape planetary environments with time, including those of Venus and Earth.”

Source: UC Riverside