After two years of successfully evading getting COVID-19 — including a few brushes with close contacts, a couple of are-they-just-colds? scares and lots of negative tests — I recently tested positive.

It felt both inevitable and shocking. I somehow avoided testing positive during the omicron surge that infected most of my friends this winter, so I figured that either I was invincible or I was next. Staring at my at-home rapid antigen test, I had to acknowledge that the long game of high-stakes tag was finally over. I was now “it.”

COVID-19 snuck up on me when I least expected it. Cases are low where I live in Queens, N.Y. And riding the subway felt low risk thanks to the federal public transit mask mandate. (A federal judge struck down the mandate on April 18, although the Biden administration announced April 20 it would appeal the ruling and some places, including New York City, are keeping masking requirements in place for the time being.) I had dined indoors, but I still wore my mask inside public spaces (SN: 3/25/22). So when I woke up with a sore throat on a Wednesday, I chalked it up to needing more sleep. Before I tested Friday evening, I was still convinced it was just another cold.

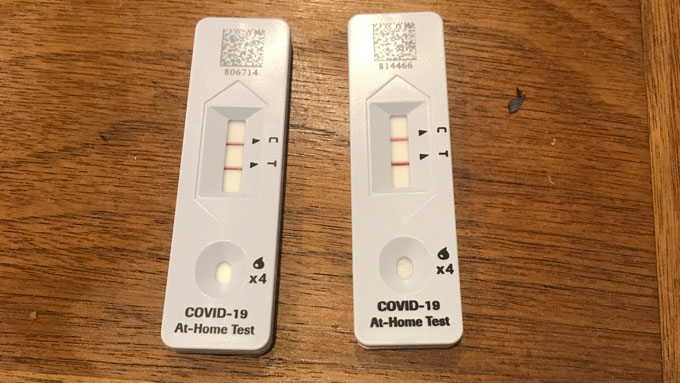

Two thick lines on my rapid test said otherwise (SN: 12/17/21). OK, I thought, I definitely have COVID. Now what?

These are my results the day I tested positive for COVID-19. I took two rapid at-home tests just to be extra sure — and then got a PCR test from a testing site so my results could be included in official case counts.A. Gibbs

These are my results the day I tested positive for COVID-19. I took two rapid at-home tests just to be extra sure — and then got a PCR test from a testing site so my results could be included in official case counts.A. Gibbs

I had a pretty good idea of the first few steps, which had been drilled into my head ad nauseam: Isolate immediately. Text close contacts from the 48 hours before first symptoms. Stay away from other people and pets in the house.

It got blurrier from there. Since I tested myself at home, my COVID-19 test wasn’t official. Surely I should report my positive test; after all, public health regulations are often based on case numbers. But it turns out that playing my part was a lot harder than I would have thought.

When it comes to reporting at-home tests, “there is no formal recommendation,” says Autumn Gertz, an epidemiologist at Boston Children’s Hospital who works on COVID-19 surveillance. Without a federal program for reporting at-home tests, states are left to their own devices, and it’s confusing to make sense of where to report, which means that many people won’t.

Sign up for e-mail updates on the latest coronavirus news and research

That’s problematic: Now that at-home tests are free and easy to access, at-home testing is becoming increasingly common. Gertz and colleagues are tracking at-home testing trends and say they have noticed a gradual increase in their use to detect COVID-19. In the coming weeks, Gertz says they expect 50 percent of people who get COVID-19 to find out from an at-home test.

Cases being underreported is nothing new. Even early on, asymptomatic and mild cases where the person never got tested wouldn’t make the case count. But at-home testing will make underreporting even more prevalent. The Institute for Health Metrics and Evaluation’s data show that only an estimated 7 percent of all U.S. COVID-19 cases are being reported, Katelyn Jetelina, an epidemiologist at the University of Texas in Dallas who writes the Your Local Epidemiologist newsletter, reports April 13 in a post titled “Can we trust case numbers?”

To make my case count, I donned two KN95 masks and walked to the COVID-19 testing booth on my street to get a PCR test that would be officially reported. (An official PCR test result may also be necessary for insurance coverage in cases that require medical care.) The downside is that I was contagious so there was a risk of exposing others to the virus, though I was masked for all but the swab. An alternative, Gertz suggests, is reporting your positive at-home test to a primary care provider. Some at-home test manufacturers also provide information about how to report results from that test.

But until public health reporting catches up with the quick transition to at-home testing, we’re flying blind. There are ways to find clues about what’s going on in your community, though.

For starters, become familiar with your local public health department website, says epidemiologist Michael Mina, the chief science officer at eMed, a company developing a system for at-home test reporting. Check to see if your community monitors wastewater, which is a better way to track the amount of SARS-CoV-2, the virus that causes COVID-19, in communities than case numbers or hospitalizations. Outbreaks Near Me, a project Gertz works on, also collects results from volunteers to help track COVID-19 trends down to the local level.

Sign Up For the Latest from Science News

Headlines and summaries of the latest Science News articles, delivered to your inbox

Client key* E-mail Address* Go

Thank you for signing up!

There was a problem signing you up.

In general, “be aware, and try to keep your eyes open for signals,” Mina says. That includes not discounting anecdotes: “If you start to hear, like, ‘Hey, you know, I’ve had a bunch of friends who are positive lately,’ that’s probably a really good indicator … that there’s a lot of COVID happening in our community right now.” And that it’s a good time to start taking extra precautions again.

Speaking of precautions, according to the isolation guidelines put out by the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, I could have returned to the world without a mask on the 10th day after my symptoms started. But I learned from Mina that you can still be contagious after 10 days. So how do I know if I can still infect others?

Turns out it’s a complicated question. There’s no magic number of days in which all people will no longer be contagious. And you can still have symptoms and not be contagious, and vice versa. But rapid at-home tests are a great indicator — albeit imperfect — of current contagiousness. (That’s unlike PCR tests, which are extremely sensitive to any remaining virus in your system long after you stop shedding it.)

How contagious a person is roughly relates to their viral load, or how many virus particles they have in their body. Early research suggested that the viral load of SARS-CoV-2 is at its highest just before or when symptoms emerge and then rapidly declines after onset of symptoms. That data informed the CDC’s decision to cut its isolation recommendation from 10 days to five days.

But several recent studies suggest that people infected during the recent COVID-19 surge continue to be contagious after five days. A preprint that studied omicron infections in NBA players found that, after five days of symptoms, about half of the players still showed significant viral load. In another preprint, Mina and researchers at the University of Chicago found that 43 percent of rapid tests from 260 vaccinated health care workers were still positive between five and 10 days after their symptoms appeared. Both studies have yet to be peer-reviewed.

See all our coverage of the coronavirus outbreak

“This isn’t like a small fraction of people who are still positive and infectious at five days,” Mina says. One possible explanation for these observations is that people who are vaccinated or have been previously infected have a quicker immune system response to the virus. So initial symptoms are caused by your immune response, not a high viral load, which comes later. “I would highly, highly, highly recommend people not listen to the five-day-to-exit-isolation recommendation,” Mina says. “That was based on old data.”

Instead, experts say, the best way to figure out whether you’re contagious after day five is by taking a rapid at-home test, which measures the amount of viral proteins in your system in real time. You can even get a sense of how infectious you are by the intensity of the positive line on your test, and the speed at which it develops. If your positive line appears quickly, chances are you have an extremely high viral load. If it takes most of the allotted test time and the line is faint, there’s likely less virus in your body.

But because it takes a lot of virus for the tests to turn positive, “you should assume that you’re infectious” if any line shows up, Mina says. Even after you’ve tested negative (twice, if possible), still avoid high-risk activities, like visiting an elderly relative.

By my 12th day in, my symptoms were mostly gone but for a lingering cough and a new proclivity for napping. But I was still testing positive on my rapid test, even though the line was much fainter than it used to be.

I wish there was an on-off switch. But, like with most things in this pandemic, it’s a squishy gray area. For all the public health recommendations, personal navigation of this virus comes down to individual everyday decisions. We hold a lot of power, and often, it feels like, not enough knowledge to make such decisions (SN: 6/16/21).

“It’s OK to be confused about all this,” Mina says. “I think a lot of people feel isolated right now and feel confused by this pandemic.” Even doctors have a hard time keeping up with the nuances and changes, he adds.

As for me, I finally tested negative 14 days after my symptoms started. Given Mina’s advice on testing negative twice, I’m still going to be careful, but I feel a little safer now.