Call it the China power paradox: while Beijing leads the world in renewable energy expansion, its coal projects are booming too.

As the top emitter of greenhouse gases, China will largely determine whether the world avoids the worst effects of climate change.

On the one hand, the picture looks positive. Gleaming solar farms now sprawl across Chinese deserts; China installed more renewables last year than all existing US capacity; and President Xi Jinping has made the country’s first emissions reduction pledges.

Yet in the first half of this year, coal power capacity also grew, with new or revived proposals hitting a decade high.

China accounted for 93% of new global coal construction in 2024, the Centre for Research on Energy and Clear Air (CREA) found.

One reason is China’s “build before breaking” approach, said Muyi Yang, senior energy analyst at think tank Ember.

Officials are wary of abandoning the old system before renewables are considered fully operational, Yang said.

“Think of it like a child learning to walk,” he told AFP.

“There will be stumbles—like supply interruptions, price spikes—and if you don’t manage those, you risk undermining public support.”

Policymakers remain scarred by 2021–22 power shortages tied to pricing, demand, grid issues and extreme weather.

While grid reform and storage would prevent a repeat, officials are hedging with new coal capacity, even if it sits idle, experts said.

“There’s the basic bureaucratic impulse to make sure that you don’t get blamed,” said Lauri Myllyvirta, CREA co-founder and lead analyst.

“They want to make absolutely sure that they don’t block one possible solution.”

Grid and transmission

There’s also an economic rationale, said David Fishman, a China power expert at Lantau Group, a consultancy.

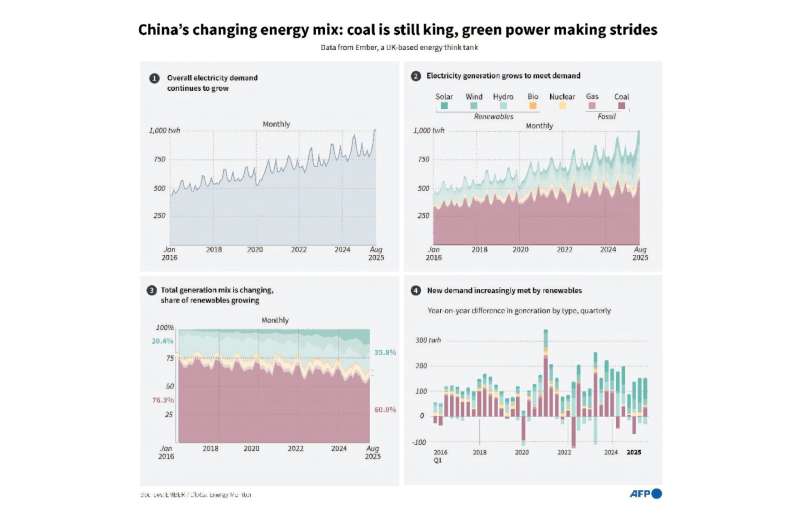

China’s electricity demand has increased faster than even record-breaking renewable installations.

That may have shifted in 2025, when renewables finally met demand growth in the first half of the year. But slower demand played a role, and many firms see coal remaining profitable.

Grid and transmission issues also make coal attractive.

Large-scale renewables are often in energy-rich, sparsely populated regions far from consumers.

Sending that power over long distances raises the cost and “incentivizes build-out of local energy capacity,” Fishman told AFP.

China is improving its infrastructure for long-distance power trading, “but it’s definitely not where it needs to be”, he added.

Coal also benefits from being a “dispatchable resource”—easily ramped up or down—unlike solar and wind, which depend on weather.

To increase renewables, “you have to make the coal plants operate more flexibly… and make space for variable renewables,” Myllyvirta said.

China’s grid remains “very rigid”, and coal-fired power plants are “the beneficiaries”, he added.

‘Instrumental’ economic driver

Other challenges loom. The end of feed-in tariffs means new renewable projects must compete on the open market.

Fishman argues that “green power demand is insufficient to keep capacity expansion high”, though the government has policy levers to tip the balance, including requiring companies to use more renewables.

China wants 3,600 gigawatts of wind and solar by 2035, but that may not meet future demand, risking further coal increases.

Still, coal additions do not always equal coal emissions—China’s fleet currently runs at only 50% capacity.

And the “clean energy” sector—including solar, wind, nuclear, hydropower, storage and EVs—is a major economic driver.

CREA estimates it contributed a record 10% to China’s gross domestic product last year, and drove a quarter of growth.

“It has become completely instrumental to meeting economic targets,” said Myllyvirta.

“That’s the main reason I’m cautiously optimistic in spite of these challenges.”

© 2025 AFP

Citation:

China’s power paradox: record renewables, continued coal (2025, October 19)

retrieved 19 October 2025

from https://techxplore.com/news/2025-10-china-power-paradox-renewables-coal.html

This document is subject to copyright. Apart from any fair dealing for the purpose of private study or research, no

part may be reproduced without the written permission. The content is provided for information purposes only.