Trees are symbols of hope, life and transformation. They’re also increasingly touted as a straightforward, relatively inexpensive, ready-for-prime-time solution to climate change.

When it comes to removing human-caused emissions of the greenhouse gas carbon dioxide from Earth’s atmosphere, trees are a big help. Through photosynthesis, trees pull the gas out of the air to help grow their leaves, branches and roots. Forest soils can also sequester vast reservoirs of carbon.

Earth holds, by one estimate, as many as 3 trillion trees. Enthusiasm is growing among governments, businesses and individuals for ambitious projects to plant billions, even a trillion more. Such massive tree-planting projects, advocates say, could do two important things: help offset current emissions and also draw out CO2 emissions that have lingered in the atmosphere for decades or longer.

Can trees save the world?

Lately, society has been putting a lot of pressure on trees to get us out of the climate change emergency we’re in. There’s no doubt that trees make life better in many respects, but there are right ways and plenty of wrong ways to protect and grow the forests.

- The first step in using trees to slow climate change: Protect the trees we have

- Mixing trees and crops can help both farmers and the climate

Even in the politically divided United States, large-scale tree-planting projects have broad bipartisan support, according to a spring 2020 poll by the Pew Research Center. And over the last decade, a diverse garden of tree-centric proposals — from planting new seedlings to promoting natural regrowth of degraded forests to blending trees with crops and pasturelands — has sprouted across the international political landscape.

Trees “are having a bit of a moment right now,” says Joe Fargione, an ecologist with The Nature Conservancy who is based in Minneapolis. It helps that everybody likes trees. “There’s no anti-tree lobby. [Trees] have lots of benefits for people. Not only do they store carbon, they help provide clean air, prevent soil erosion, shade and shelter homes to reduce energy costs and give people a sense of well-being.”

Conservationists are understandably eager to harness this enthusiasm to combat climate change. “We’re tapping into the zeitgeist,” says Justin Adams, executive director of the Tropical Forest Alliance at the World Economic Forum, an international nongovernmental organization based in Geneva. In January 2020, the World Economic Forum launched the One Trillion Trees Initiative, a global movement to grow, restore and conserve trees around the planet. One trillion is also the target for other organizations that coordinate global forestation projects, such as Plant-for-the-Planet’s Trillion Tree Campaign and Trillion Trees, a partnership of the World Wildlife Fund, the Wildlife Conservation Society and other conservation groups.

A carbon-containing system

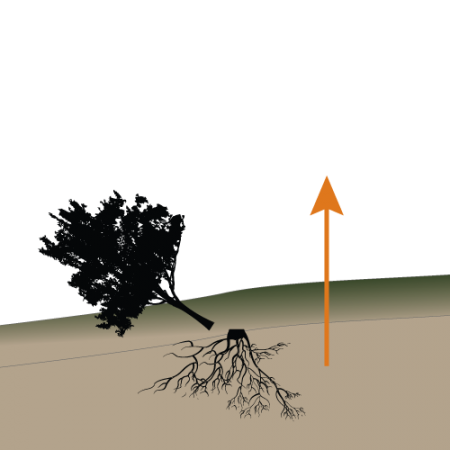

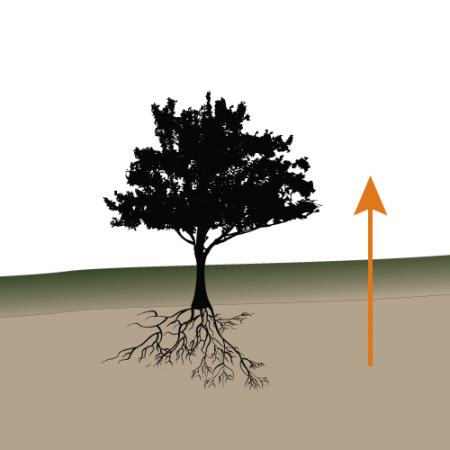

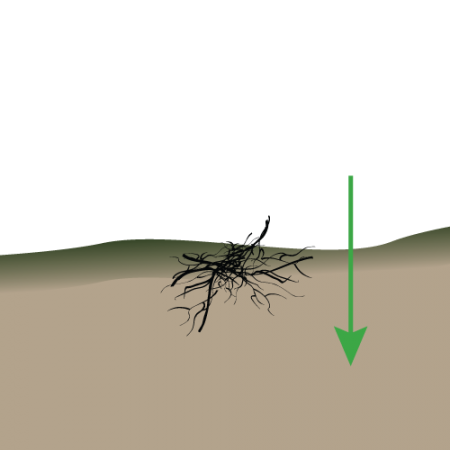

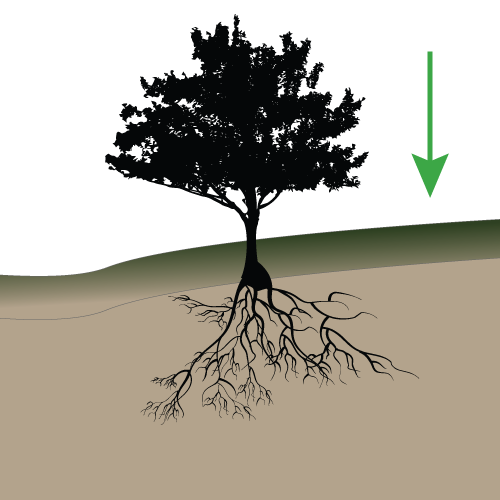

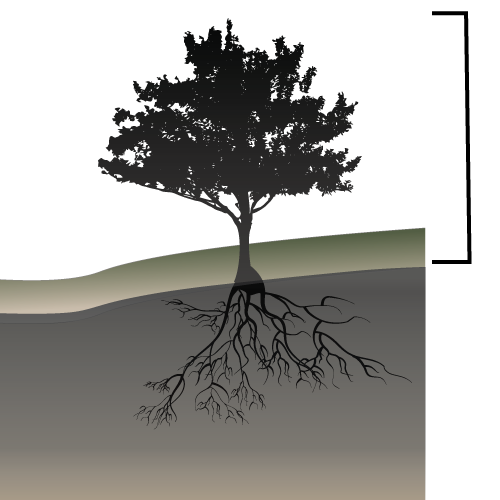

Forests store carbon aboveground and below. That carbon returns to the atmosphere by microbial activity in the soil, or when trees are cut down and die.

Trees removed from forests can cause carbon losses through fire, processing, soil erosion and decomposition

Trees removed from forests can cause carbon losses through fire, processing, soil erosion and decomposition  Respiration in the soil, by microbes and other organisms, returns carbon to the atmosphere

Respiration in the soil, by microbes and other organisms, returns carbon to the atmosphere  Leaf litter adds carbon to soil and retains moisture and nutrients

Leaf litter adds carbon to soil and retains moisture and nutrients  Trees and other vegetation take up atmospheric carbon through photosynthesis

Trees and other vegetation take up atmospheric carbon through photosynthesis  Carbon is aboveground in branches, trunk, foliage

Carbon is aboveground in branches, trunk, foliage  Carbon is belowground in leaf litter, roots, soil, fungi, bacteria SOURCE: MINNESOTA BOARD OF WATER AND SOIL RESOURCES 2019; images: T. Tibbitts

Carbon is belowground in leaf litter, roots, soil, fungi, bacteria SOURCE: MINNESOTA BOARD OF WATER AND SOIL RESOURCES 2019; images: T. Tibbitts

Yet, as global eagerness for adding more trees grows, some scientists are urging caution. Before moving forward, they say, such massive tree projects must address a range of scientific, political, social and economic concerns. Poorly designed projects that don’t address these issues could do more harm than good, the researchers say, wasting money as well as political and public goodwill. The concerns are myriad: There’s too much focus on numbers of seedlings planted, and too little time spent on how to keep the trees alive in the long term, or in working with local communities. And there’s not enough emphasis on how different types of forests sequester very different amounts of carbon. There’s too much talk about trees, and not enough about other carbon-storing ecosystems.

“There’s a real feeling that … forests and trees are just the idea we can use to get political support” for many, perhaps more complicated, types of landscape restoration initiatives, says Joseph Veldman, an ecologist at Texas A&M University in College Station. But that can lead to all kinds of problems, he adds. “For me, the devil is in the details.”

Sign Up For the Latest from Science News

Headlines and summaries of the latest Science News articles, delivered to your inbox

Client key* E-mail Address* Go

Thank you for signing up!

There was a problem signing you up.

The root of the problem

The pace of climate change is accelerating into the realm of emergency, scientists say. Over the last 200 years, human-caused emissions of greenhouse gases, including CO2 and methane, have raised the average temperature of the planet by about 1 degree Celsius (SN: 12/22/18 & 1/5/19, p. 18).

The litany of impacts of this heating is familiar by now. Earth’s poles are rapidly shedding ice, which raises sea levels; the oceans are heating up, threatening fish and food security. Tropical storms are becoming rainier and lingering longer, and out of control wildfires are blazing from the Arctic to Australia (SN: 12/19/20 & 1/2/21, p. 32).

The world’s oceans and land-based ecosystems, such as forests, absorb about half of the carbon emissions from fossil fuel burning and other industrial activities. The rest goes into the atmosphere. So “the majority of the solution to climate change will need to come from reducing our emissions,” Fargione says. To meet climate targets set by the 2015 Paris Agreement, much deeper and more painful cuts in emissions than nations have pledged so far will be needed in the next 10 years.

We invest a lot in tree plantings, but we are not sure what happens after that.

Lalisa Duguma

But increasingly, scientists warn that reducing emissions alone won’t be enough to bring Earth’s thermostat back down. “We really do need an all-hands-on-deck approach,” Fargione says. Specifically, researchers are investigating ways to actively remove that carbon, known as negative emissions technologies. Many of these approaches, such as removing CO2 directly from the air and converting it into fuel, are still being developed.

But trees are a ready kind of negative emissions “technology,” and many researchers see them as the first line of defense. In its January 2020 report, “CarbonShot,” the World Resources Institute, a global nonprofit research organization, suggested that large and immediate investments in reforestation within the United States will be key for the country to have any hope of reaching carbon neutrality — in which ongoing carbon emissions are balanced by carbon withdrawals — by 2050. The report called for the U.S. government to invest $4 billion a year through 2030 to support tree restoration projects across the United States. Those efforts would be a bridge to a future of, hopefully, more technologies that can pull large amounts of carbon out of the atmosphere.

The numbers game

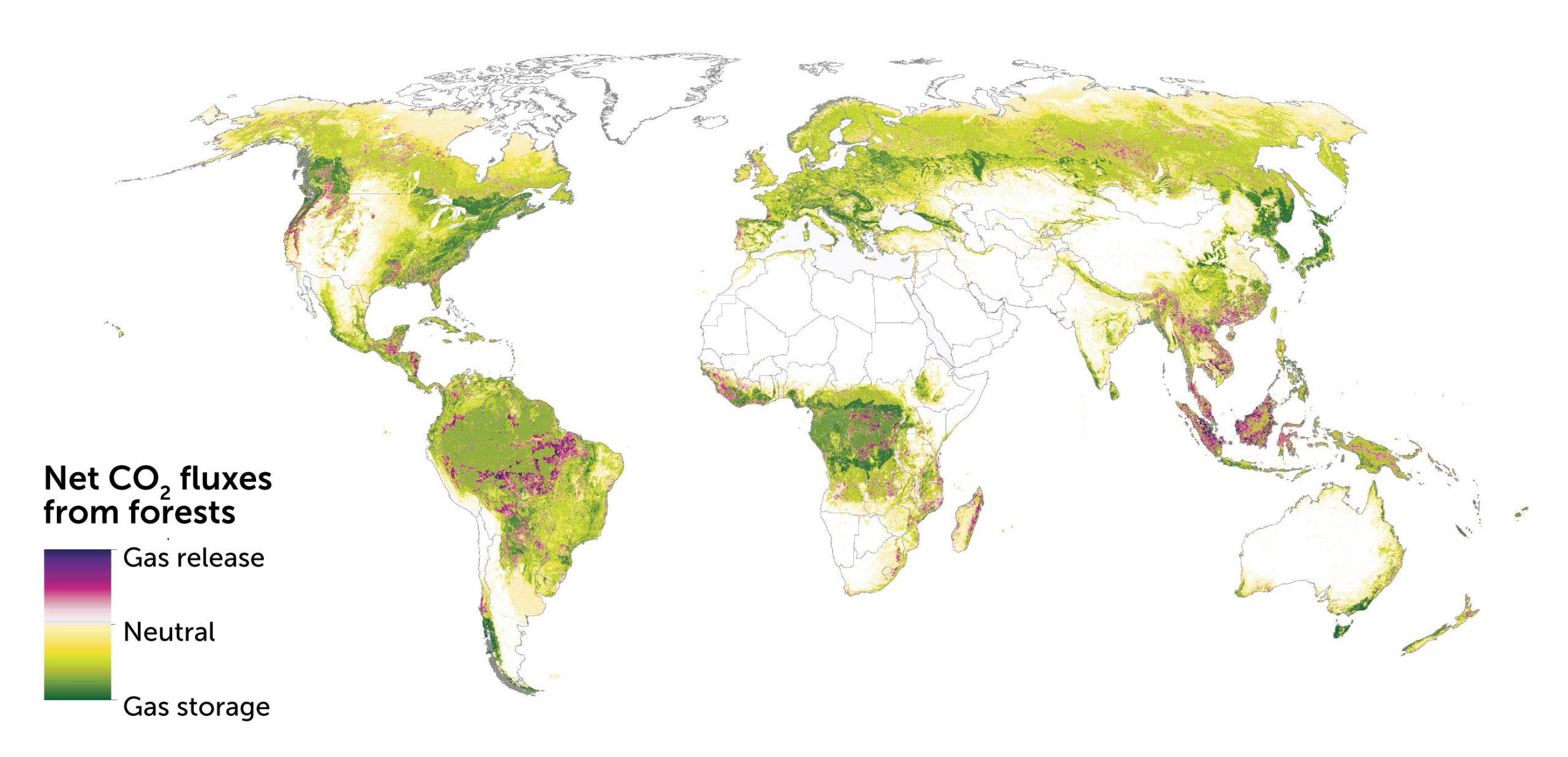

Earth’s forests absorb, on average, 16 billion metric tons of CO2 annually, researchers reported in the March Nature Climate Change. But human activity can turn forests into sources of carbon: Thanks to land clearing, wildfires and the burning of wood products, forests also emit an estimated 8.1 billion tons of the gas back to the atmosphere.

That leaves a net amount of 7.6 billion tons of CO2 absorbed by forests per year — roughly a fifth of the 36 billion tons of CO2 emitted by humans in 2019. Deforestation and forest degradation are rapidly shifting the balance. Forests in Southeast Asia now emit more carbon than they absorb due to clearing for plantations and uncontrolled fires. The Amazon’s forests may flip from carbon sponge to carbon source by 2050, researchers say (SN Online: 1/10/20). The priority for slowing climate change, many agree, should be saving the trees we have.

Forests in flux

While global forests were a net carbon sink of about 7.6 gigatons of carbon dioxide per year from 2001 to 2019, forests in areas such as Southeast Asia and parts of the Amazon began releasing more carbon than they store.

Tap map to enlarge

Net annual average contribution of carbon dioxide from Earth’s forests, 2001–2019

SOURCE: N.L. HARRIS ET AL/NATURE CLIMATE CHANGE 2021

SOURCE: N.L. HARRIS ET AL/NATURE CLIMATE CHANGE 2021

Just how many more trees might be mustered for the fight is unclear, however. In 2019, Thomas Crowther, an ecologist at ETH Zurich, and his team estimated in Science that around the globe, there are 900 million hectares of land — an area about the size of the United States — available for planting new forests and reviving old ones (SN: 8/17/19, p. 5). That land could hold over a trillion more trees, the team claimed, which could trap about 206 billion tons of carbon over a century.

That study, led by Jean-Francois Bastin, then a postdoc in Crowther’s lab, was sweeping, ambitious and hopeful. Its findings spread like wildfire through media, conservationist and political circles. “We were in New York during Climate Week [2019], and everybody’s talking about this paper,” Adams recalls. “It had just popped into people’s consciousness, this unbelievable technology solution called the tree.”

To channel that enthusiasm, the One Trillion Trees Initiative incorporated the study’s findings into its mission statement, and countless other tree-planting efforts have cited the report.

But critics say the study is deeply flawed, and that its accounting — of potential trees, of potential carbon uptake — is not only sloppy, but dangerous. In 2019, Science published five separate responses outlining numerous concerns. For example, the study’s criteria for “available” land for tree planting were too broad, and the carbon accounting was inaccurate because it assumes that new tree canopy cover equals new carbon storage. Savannas and natural grasslands may have relatively few trees, critics noted, but these regions already hold plenty of carbon in their soils. When that carbon is accounted for, the carbon uptake benefit from planting trees drops to perhaps a fifth of the original estimate.

Trees are having a bit of a moment right now.

Joe Fargione

There’s also the question of how forests themselves can affect the climate. Adding trees to snow-covered regions, for example, could increase the absorption of solar radiation, possibly leading to warming.

“Their numbers are just so far from anything reasonable,” Veldman says. And focusing on the number of trees planted also sets up another problem, he adds — an incentive structure that is prone to corruption. “Once you set up the incentive system, behaviors change to basically play that game.”

Adams acknowledges these concerns. But, the One Trillion Trees Initiative isn’t really focused on “the specifics of the math,” he says, whether it’s the number of trees or the exact amount of carbon sequestered. The goal is to create a powerful climate movement to “motivate a community behind a big goal and a big vision,” he says. “It could give us a fighting chance to get restoration right.”

Other nonprofit conservation groups, like the World Resources Institute and The Nature Conservancy, are trying to walk a similar line in their advocacy. But some scientists are skeptical that governments and policy makers tasked with implementing massive forest restoration programs will take note of such nuances.

“I study how government bureaucracy works,” says Forrest Fleischman, who researches forest and environmental policy at the University of Minnesota in St. Paul. Policy makers, he says, are “going to see ‘forest restoration,’ and that means planting rows of trees. That’s what they know how to do.”

Counting carbon

How much carbon a forest can draw from the atmosphere depends on how you define “forest.” There’s reforestation — restoring trees to regions where they used to be — and afforestation — planting new trees where they haven’t historically been. Reforestation can mean new planting, including crop trees; allowing forests to regrow naturally on lands previously cleared for agriculture or other purposes; or blending tree cover with croplands or grazing areas.

In the past, the carbon uptake potential of letting forests regrow naturally was underestimated by 32 percent, on average — and by as much as 53 percent in tropical forests, according to a 2020 study in Nature. Now, scientists are calling for more attention to this forestation strategy.

If it’s just a matter of what’s best for the climate, natural forest regrowth offers the biggest bang for the buck, says Simon Lewis, a forest ecologist at University College London. Single-tree commercial crop plantations, on the other hand, may meet the technical definition of a “forest” — a certain concentration of trees in a given area — but factor in land clearing to plant the crop and frequent harvesting of the trees, and such plantations can actually release more carbon than they sequester.

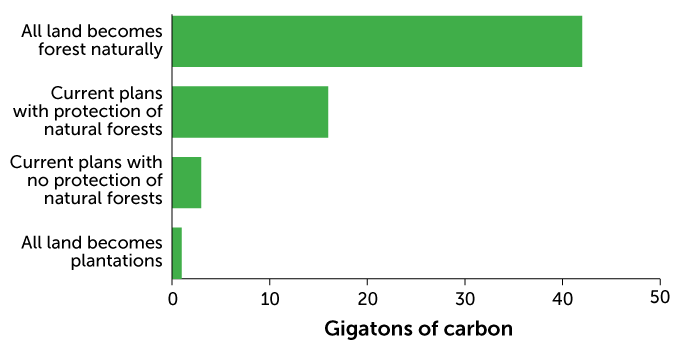

Comparing the carbon accounting between different restoration projects becomes particularly important in the framework of international climate targets and challenges. For example, the 2011 Bonn Challenge is a global project aimed at restoring 350 million hectares by 2030. As of 2020, 61 nations had pledged to restore a total of 210 million hectares of their lands. The potential carbon impact of the stated pledges, however, varies widely depending on the specific restoration plans.

Levels of protection

The Bonn Challenge aims to globally reforest 350 million hectares of land. Allowing all to regrow naturally would sequester 42 gigatons of carbon by 2100. Pledges of 43 tropical and subtropical nations that joined by 2019 — a mix of plantations and natural regrowth — would sequester 16 gigatons of carbon. If some of the land is later converted to biofuel plantations, sequestration is 3 gigatons. With only plantations, carbon storage is 1 gigaton.

Amount of carbon sequestered by 2100 in four Bonn Challenge scenarios

SOURCE: S.L. LEWIS ET AL/NATURE 2019; graphs: T. Tibbitts

SOURCE: S.L. LEWIS ET AL/NATURE 2019; graphs: T. Tibbitts

In a 2019 study in Nature, Lewis and his colleagues estimated that if all 350 million hectares were allowed to regrow natural forest, those lands would sequester about 42 billion metric tons (gigatons in chart above) of carbon by 2100. Conversely, if the land were to be filled with single-tree commercial crop plantations, carbon storage drops to about 1 billion metric tons. And right now, plantations make up a majority of the restoration plans submitted under the Bonn Challenge.

Striking the right balance between offering incentives to landowners to participate while also placing certain restrictions remains a tricky and long-standing challenge, not just for combating the climate emergency but also for trying to preserve biodiversity (SN: 8/1/20, p. 18). Since 1974, Chile, for example, has been encouraging private landowners to plant trees through subsidies. But landowners are allowed to use these subsidies to replace native forestlands with profitable plantations. As a result, Chile’s new plantings not only didn’t increase carbon storage, they also accelerated biodiversity losses, researchers reported in the September 2020 Nature Sustainability.

The reality is that plantations are a necessary part of initiatives like the Bonn Challenge, because they make landscape restoration economically viable for many nations, Lewis says. “Plantations can play a part, and so can agroforestry as well as areas of more natural forest,” he says. “It’s important to remember that landscapes provide a whole host of services and products to people who live there.”

But he and others advocate for increasing the proportion of forestation that is naturally regenerated. “I’d like to see more attention on that,” says Robin Chazdon, a forest ecologist affiliated with the University of the Sunshine Coast in Australia as well as with the World Resources Institute. Naturally regenerated forests could be allowed to grow in buffer regions between farms, creating connecting green corridors that could also help preserve biodiversity, she says. And “it’s certainly a lot less expensive to let nature do the work,” Chazdon says.

Indeed, massive tree-planting projects may also be stymied by pipeline and workforce issues. Take seeds: In the United States, nurseries produce about 1.3 billion seedlings per year, Fargione and colleagues calculated in a study reported February 4 in Frontiers in Forests and Global Change. To support a massive tree-planting initiative, U.S. nurseries would need to at least double that number.

A tree-planting report card

From China to Turkey, countries around the world have launched enthusiastic national tree-planting efforts. And many of them have become cautionary tales.

China kicked off a campaign in 1978 to push back the encroaching Gobi Desert, which has become the fastest-growing desert on Earth due to a combination of mass deforestation and overgrazing, exacerbated by high winds that drive erosion. China’s Three-North Shelter Forest Program, nicknamed the Great Green Wall, aims to plant a band of trees stretching 4,500 kilometers across the northern part of the country. The campaign has involved millions of seeds dropped from airplanes and millions more seedlings planted by hand. But a 2011 analysis suggested that up to 85 percent of the plantings had failed because the nonnative species chosen couldn’t survive in the arid environments they were plopped into.

A woman places straw in March 2019 to fix sand in place before planting trees at the edge of the Gobi Desert in China’s Minqin County. Her work is part of a private tree-planting initiative that dovetails with the government’s decades-long effort to build a “green wall” to hold back the desert.WANG HE/GETTY IMAGES PLUS

A woman places straw in March 2019 to fix sand in place before planting trees at the edge of the Gobi Desert in China’s Minqin County. Her work is part of a private tree-planting initiative that dovetails with the government’s decades-long effort to build a “green wall” to hold back the desert.WANG HE/GETTY IMAGES PLUS

More recently, Turkey launched its own reforestation effort. On November 11, 2019, National Forestation Day, volunteers across the country planted 11 million trees at more than 2,000 sites. In Turkey’s Çorum province, 303,150 saplings were planted in a single hour, setting a new world record.

Within three months, however, up to 90 percent of the new saplings inspected by Turkey’s agriculture and forestry trade union were dead, according to the union’s president, Şükrü Durmuş, speaking to the Guardian (Turkey’s minister of agriculture and forestry denied that this was true). The saplings, Durmuş said, died due to a combination of insufficient water and because they were planted at the wrong time of year, and not by experts.

Some smaller-scale efforts also appear to be failing, though less spectacularly. Tree planting has been ongoing for decades in the Kangra district of Himachal Pradesh in northern India, says Eric Coleman, a political scientist at Florida State University in Tallahassee, who’s been studying the outcomes. The aim is to increase the density of the local forests and provide additional forest benefits for communities nearby, such as wood for fuel and fodder for grazing animals. How much money was spent isn’t known, Coleman says, because there aren’t records of how much was paid for seeds. “But I imagine it was in the millions and millions of dollars.”

Coleman and his colleagues analyzed satellite images and interviewed members of the local communities. They found that the tree planting had very little impact one way or the other. Forest density didn’t change much, and the surveys suggested that few households were gaining benefits from the planted forests, such as gathering wood for fuel, grazing animals or collecting fodder.

But massive tree-planting efforts don’t have to fail. “It’s easy to point to examples of large-scale reforestation efforts that weren’t using the right tree stock, or adequately trained workforces, or didn’t have enough investment in … postplanting treatments and care,” Fargione says. “We … need to learn from those efforts.”

Speak for the trees

Forester Lalisa Duguma of World Agroforestry in Nairobi, Kenya, and colleagues explored some of the reasons for the very high failure rates of these projects in a working paper in 2020. “Every year there are billions of dollars invested [in tree planting], but forest cover is not increasing,” Duguma says. “Where are those resources going?”

Trees can buy time for tech testing

If done right, planting trees might give researchers time to develop some of these carbon-capture technologies.

Bioenergy with carbon capture and sequestration

Plant biomass is used to produce electricity, fuel or heat. Any CO2 released is captured and stored.

Direct air capture

Chemical processes that capture CO2 from ambient air and concentrate it, so that it can be injected into a storage reservoir.

Carbon mineralization

Through chemical reactions, CO2 from the atmosphere becomestrapped in existing rock.

Geologic sequestration

CO2 is captured and injected into deep underground formations.

images: T. Tibbitts

In 2019, Duguma raised this question at the World Congress on Agroforestry in Montpellier, France. He asked the audience of scientists and conservationists: “How many of you have ever planted a tree seedling?” To those who raised their hands, he asked, “Have they grown?”

Some respondents acknowledged that they weren’t sure. “Very good! That’s what I wanted,” he told them. “We invest a lot in tree plantings, but we are not sure what happens after that.”

It comes down to a deceptively simple but “really fundamental” point, Duguma says. “The narrative has to change — from tree planting to tree growing.”

The good news is that this point has begun to percolate through the conservationist world, he says. To have any hope of success, restoration projects need to consider the best times of year to plant seeds, which seeds to plant and where, who will care for the seedlings as they grow into trees, how that growth will be monitored, and how to balance the economic and environmental needs of people in developing countries where the trees might be planted.

“That is where we need to capture the voice of the people,” Duguma says. “From the beginning.”

Even as the enthusiasm for tree planting takes root in the policy world, there’s a growing awareness among researchers and conservationists that local community engagement must be built into these plans; it’s indispensable to their success.

“It will be almost impossible to meet these targets we all care so much about unless small farmers and communities benefit more from trees,” as David Kaimowitz of the United Nations’ Food and Agriculture Organization wrote March 19 in a blog post for the London-based nonprofit International Institute for Environment and Development.

For one thing, farmers and villagers managing the land need incentives to care for the plantings and that includes having clear rights to the trees’ benefits, such as food or thatching or grazing. “People who have insecure land tenure don’t plant trees,” Fleischman says.

Fleischman and others outlined many of the potential social and economic pitfalls of large-scale tree-planting projects last November in BioScience. Those lessons boil down to this, Fleischman says: “You need to know something about the place … the political dynamics, the social dynamics.… It’s going to be very different in different parts of the world.”

The old cliché — think globally, act locally — may offer the best path forward for conservationists and researchers trying to balance so many different needs and still address climate change.

“There are a host of sociologically and biologically informed approaches to conservation and restoration that … have virtually nothing to do with tree planting,” Veldman says. “An effective global restoration agenda needs to encompass the diversity of Earth’s ecosystems and the people who use them.”

Trustworthy journalism comes at a price.

Scientists and journalists share a core belief in questioning, observing and verifying to reach the truth. Science News reports on crucial research and discovery across science disciplines. We need your financial support to make it happen – every contribution makes a difference.

Subscribe or Donate Now