Glioblastomas are the deadliest form of malignant brain tumor, and most patients diagnosed with the disease live only one or two years. In these tumors, normal cells in the brain become aggressive, growing rapidly and invading the surrounding tissue. The resulting cancer cells are metabolically different from their neighboring healthy cells.

In a study published in Nature, researchers from the University of Michigan tracked how glucose is used in glioblastoma tumor cells.

The team, a partnership between the Rogel Cancer Center, Department of Neurosurgery and the Department of Biomedical Engineering, discovered that brain tumors differ in how they consume certain nutrients in diets.

“We altered the diet in mouse models and were able to significantly slow down and block the growth of these tumors,” said co-senior author Daniel Wahl, M.D., Ph.D., associate professor of radiation oncology. “Our study may help create new treatment opportunities for patients in the near future.”

Conventional treatments consist of surgery followed by radiation therapy and chemotherapy. However, the tumors eventually return and become resistant to treatment. Previously, researchers have shown that resistance is due to metabolic rewiring within cancer cells.

Cancer cells in the brain use sugars differently compared to healthy cells

Metabolism is the process by which our bodies break down molecules like carbohydrates and proteins so that our cells can either use them or build new molecules.

Although both brain and cancer cells depend on sugar, the team wanted to see if they use sugar differently. They injected small amounts of labeled sugar into mice and, importantly, into patients with brain tumors to follow how it is used.

“To really understand these brain cancers and improve treatments for patients, we needed to do the hard work of studying the tumors in patients themselves, not just in the lab,” said co-senior author Wajd Al-Holou, M.D., a brain tumor neurosurgeon who co-directs the Michigan Multidisciplinary Brain Tumor Clinic.

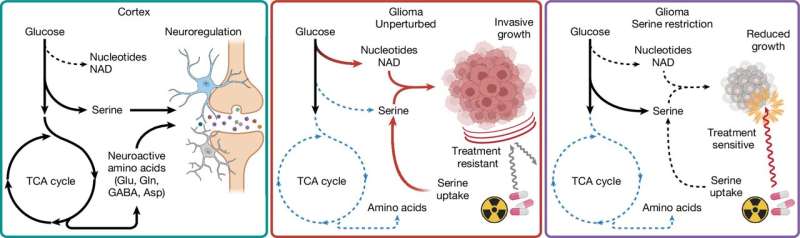

Although both normal tissues and tumor cells used a lot of sugar, they used it for different purposes. “It’s a metabolic fork in the road,” said Andrew Scott, Ph.D., a research scholar in Wahl’s lab. “The brain channels sugar into energy production and neurotransmitters for thinking and health, but tumors redirect sugar to make materials for more cancer cells.”

The team found that healthy tissues used sugars to generate energy and make chemicals that allow the brain to function properly. Glioblastomas, on the other hand, turned off those processes and instead converted sugar into molecules like nucleotides—the building blocks of DNA and RNA—that helped them grow and invade the surrounding tissues.

Amino-acid restricted diets can improve treatment outcomes in mice

The researchers also noticed other important differences. The normal brain used sugar to make amino acids, the building blocks of proteins. However, brain cancers seemed to turn this pathway off and instead scavenged these amino acids from the blood.

This finding led the researchers to consider whether lowering the levels of certain amino acids in the blood could affect brain cancer without affecting the normal brain. They tested whether mice that were fed an amino acid-restricted diet had better treatment outcomes.

“When we got rid of the amino acids serine and glycine in the mice, their response to radiation and chemotherapy was better and the tumors were smaller than the control mice that were fed serine,” said co-senior author Deepak Nagrath, Ph.D. professor of biomedical engineering.

Based on their measurements in mice, the team also built mathematical models that can track how glucose is being used in different pathways, which can help identify other drug targets.

Co-senior author Costas Lyssiotis, Ph.D., professor of molecular and integrative physiology, compared metabolic pathways to roads and drugs to roadblocks. “Dropping a roadblock on a fast highway with a lot of traffic will have a greater effect than blocking a country road with a lower speed limit and only a few cars.

“Similarly, in a normal brain, the uptake of the amino acid serine from the blood is like a slow country road. But brain cancer is like a busy freeway, giving researchers the opportunity to selectively target the cancer.”

The team is working on opening clinical trials soon to test whether specialized diets that limit blood serine levels can also help glioblastoma patients. “This is a multidisciplinary effort from across the university,” Wahl said.

“It is a study that no individual investigator could do on their own and I’m grateful to be part of a team that works together to make important discoveries that can improve treatments for our patients.”

More information:

Andrew J. Scott et al, Rewiring of cortical glucose metabolism fuels human brain cancer growth, Nature (2025). DOI: 10.1038/s41586-025-09460-7

Citation:

Dietary changes could provide a therapeutic avenue for brain cancer (2025, September 4)

retrieved 4 September 2025

from https://medicalxpress.com/news/2025-09-dietary-therapeutic-avenue-brain-cancer.html

This document is subject to copyright. Apart from any fair dealing for the purpose of private study or research, no

part may be reproduced without the written permission. The content is provided for information purposes only.