One of the most infamous psychology experiments ever conducted involved a carefully planned form of child abuse. The study rested on a simple scheme that would never get approved or funded today. In 1920, two researchers reported that they had repeatedly startled an unsuspecting infant, who came to be known as Little Albert, to see if he could be conditioned like Pavlov’s dogs.

Psychologist John Watson of Johns Hopkins University and his graduate student Rosalie Rayner viewed their laboratory fearfest as a step toward strengthening a branch of natural science able to predict and control the behavior of people and other animals.

At first, the 9-month-old boy, identified as Albert B., sat placidly when the researchers placed a white rat in front of him. In tests two months later, one researcher presented the rodent, and just as the child brought his hand to pet it, the other scientist stood behind Albert and clanged a metal rod with a hammer. Their goal: to see if a child could be conditioned to associate an emotionally neutral white rat with a scary noise, just as Russian physiologist Ivan Pavlov had trained dogs to associate the meaningless clicks of a metronome with the joy of being fed.

Pavlov’s dogs slobbered at the mere sound of a metronome. Likewise, Little Albert eventually cried and recoiled at the mere sight of a white rat. The boy’s conditioned fear wasn’t confined to rodents. He got upset when presented with other furry things — a rabbit, a dog, a fur coat and a Santa Claus mask with a fuzzy beard.

In a questionable experiment published in 1920, researchers conditioned an infant nicknamed Little Albert to fear various furry animals and objects.J.B. Watson

In a questionable experiment published in 1920, researchers conditioned an infant nicknamed Little Albert to fear various furry animals and objects.J.B. Watson

Crucial details of the Little Albert experiment remain unclear or in dispute, such as who the child was, whether he had any neurological conditions and why the boy was removed from the experiment, possibly by his mother, before the researchers could attempt to reverse his learned fears. Also uncertain is whether he experienced any long-term effects of his experience.

Although experimental psychology originated in Germany in 1879, Watson’s notorious study foreshadowed a messy, contentious approach to the “science of us” that has played out over the last 100 years. Warring scientific tribes armed with clashing assumptions about how people think and behave have struggled for dominance in psychology and other social sciences. Some have achieved great influence and popularity, at least for a while. Others have toiled in relative obscurity. Competing tribes have rarely joined forces to develop or integrate theories about how we think or why we do what we do; such efforts don’t attract much attention.

But Watson, who had a second career as a successful advertising executive, knew how to grab the spotlight. He pioneered a field dubbed behaviorism, the study of people’s external reactions to specific sensations and situations. Only behavior counted in Watson’s science. Unobservable thoughts didn’t concern him.

To celebrate our 100th anniversary, we’re highlighting some of the biggest advances in science over the last century. To see an expanded version of this story, visit Century of Science: The science of us.

READ MORE

Even as behaviorism took center stage — Watson wrote a best-selling book on how to raise children based on conditioning principles — some psychologists addressed mental life. American psychologist Edward Tolman concluded that rats learned the spatial layout of mazes by constructing a “cognitive map” of their surroundings (SN: 3/29/47, p. 199). Beginning in the 1910s, Gestalt psychologists studied how we perceive wholes differently than the sum of their parts, such as, depending on your perspective, seeing either a goblet or the profiles of two faces in the foreground of a drawing (SN: 5/18/29, p. 306).

And starting at the turn of the 20th century, Sigmund Freud, the founder of psychoanalysis, exerted a major influence on the treatment of psychological ailments through his writings on topics such as unconscious conflicts, neuroses and psychoses (SN: 7/9/27, p. 21). Freudian clinicians guided the drafting of the American Psychiatric Association’s first official classification system for mental disorders. Later editions of the psychiatric “bible” dropped Freudian concepts as unscientific — he had based his ideas on analyses of himself and his patients, not on lab studies.

Shortly after Freud’s intellectual star rose, so did that of Harvard University psychologist B.F. Skinner, who could trace his academic lineage back to Watson’s behaviorism. By placing rats and pigeons in conditioning chambers known as Skinner boxes, Skinner studied how the timing and rate of rewards or punishments affect animals’ ability to learn new behaviors. He found, for instance, that regular rewards speed up learning, whereas intermittent rewards produce behavior that’s hard to extinguish in the lab. He also stirred up controversy by calling free will an illusion and imagining a utopian society in which communities doled out rewards to produce well-behaved citizens.

Skinner’s ideas, and behaviorism in general, lost favor by the late 1960s (SN: 9/11/71, p. 166). Scientists began to entertain the idea that computations, or statistical calculations, in the brain might enable thinking.

Psychologist B.F. Skinner (far left) studied how rewards and punishments shape new behaviors in pigeons and other animals.Science History Images/Alamy Stock Photo

Psychologist B.F. Skinner (far left) studied how rewards and punishments shape new behaviors in pigeons and other animals.Science History Images/Alamy Stock Photo  Enclosed chambers known as Skinner boxes, originally used to condition behaviors in nonhuman animals, later became confused with a different Skinner invention that wasn’t used for research, a climate-controlled crib for human infants.Science History Images/Alamy Stock Photo

Enclosed chambers known as Skinner boxes, originally used to condition behaviors in nonhuman animals, later became confused with a different Skinner invention that wasn’t used for research, a climate-controlled crib for human infants.Science History Images/Alamy Stock Photo

At the same time, some psychologists suspected that human judgments relied on faulty mental shortcuts rather than computer-like data crunching. Research on allegedly rampant flaws in how people make decisions individually and in social situations shot to prominence in the 1970s and remains popular today. In the last few decades, an opposing line of research has reported that instead, people render good judgments by using simple rules of thumb tailored to relevant situations.

Starting in the 1990s, the science of us branched out in new directions. Progress has been made in studying how emotional problems develop over decades, how people in non-Western cultures think and why deaths linked to despair have steadily risen in the United States. Scientific attention has also been redirected to finding new, more precise ways to define mental disorders.

No unified theory of mind and behavior unites these projects. For now, as social psychologists William Swann of the University of Texas at Austin and Jolanda Jetten of the University of Queensland in Australia wrote in 2017, perhaps scientists should broaden their perspectives to “witness the numerous striking and ingenious ways that the human spirit asserts itself.”

Sign Up For the Latest from Science News

Headlines and summaries of the latest Science News articles, delivered to your inbox

Client key* E-mail Address* Go

Thank you for signing up!

There was a problem signing you up.

Revolution and rationality

Today’s focus on studying people’s thoughts and feelings as well as their behaviors can be traced to a “cognitive revolution” that began in the mid-20th century.

The rise of increasingly powerful computers motivated the idea that complex programs in the brain guide “information processing” so that we can make sense of the world. These neural programs, or sets of formal rules, provide frameworks for remembering what we’ve done, learning a native language and performing other mental feats, a new breed of cognitive and computer scientists argued (SN: 11/26/88, p. 345).

Economists adapted the cognitive science approach to their own needs. They were already convinced that individuals calculate costs and benefits of every transaction in the most self-serving ways possible — or should do so but can’t due to human mental limitations. Financial theorists bought into the latter argument and began creating cost-benefit formulas for investing money that are far too complex for anyone to think up, much less calculate, on their own. Economist Harry Markowitz won the Nobel Memorial Prize in Economic Sciences in 1990 for his set of mathematical rules, introduced in 1952, to allocate an investor’s money to different assets, with more cash going to better and safer bets.

But in the 1970s, psychologists began conducting studies documenting that people rarely think according to rational rules of logic beloved by economists. Psychologists Daniel Kahneman of Princeton University, who received the Nobel Memorial Prize in Economic Sciences in 2002, and Amos Tversky of Stanford University founded that area of research, at first called heuristics (meaning mental shortcuts) and biases.

Amos Tversky (left) and Daniel Kahneman (right) started a popular line of research in the 1970s aimed at uncovering ways in which human decisions go awry.Barbara Tversky

Amos Tversky (left) and Daniel Kahneman (right) started a popular line of research in the 1970s aimed at uncovering ways in which human decisions go awry.Barbara Tversky

Kahneman and Tversky popularized the notion that decision makers rely on highly fallible mental shortcuts that can have dire consequences. For instance, people bet themselves into bankruptcy at blackjack tables based on what they easily remember — big winners — rather than on the vast majority of losers. University of Chicago economist Richard Thaler applied that idea to the study of financial behavior in the 1980s. He was awarded the 2017 Nobel Memorial Prize in Economic Sciences for his contributions to the field of behavioral economics, which incorporated previous heuristics and biases research. Thaler has championed the practice of nudging, in which government and private institutions find ways to prod people to make decisions deemed to be in their best interest.

Better to nudge, behavioral economists argue, than to leave people to their potentially disastrous mental shortcuts. Nudges have been used, for instance, to enroll employees automatically in retirement savings plans unless they opt out. That tactic is aimed at preventing delays in saving money during prime work years that lead to financial troubles later in life.

Another nudge tactic attempts to reduce overeating of sweets and other unhealthy foods, and perhaps rising obesity rates as well, by redesigning cafeterias and grocery stores so that vegetables and other nutritious foods are easiest to see and reach.

As nudging gained in popularity, Kahneman and Tversky’s research also stimulated the growth of an opposing research camp, founded in the 1990s by psychologist Gerd Gigerenzer, now director of the Harding Center for Risk Literacy at the University of Potsdam in Germany (SN: 7/13/96, p. 24).

In the 1990s, psychologist Gerd Gigerenzer and colleagues launched investigations of simple but powerful decision-making shortcuts.Franz Johann Morgenbesser/Flickr (CC BY-SA 2.0)

In the 1990s, psychologist Gerd Gigerenzer and colleagues launched investigations of simple but powerful decision-making shortcuts.Franz Johann Morgenbesser/Flickr (CC BY-SA 2.0)

Gigerenzer and colleagues study simple rules of thumb that, when geared toward crucial cues in real-world situations, work remarkably well for decision making. Their approach builds on ideas on decision making in organizations that won economist Herbert Simon the 1978 Nobel Memorial Prize in Economic Sciences (SN: 10/21/78, p. 277).

In the real world, people typically possess limited information and have little time to make decisions, Gigerenzer argues. Precise risks can’t be known in advance or calculated based on what’s happened in the past because many interacting factors can trigger unexpected events in, for example, one’s life or the world economy. Amid so much uncertainty, simple but powerful decision tactics can outperform massive number-crunching operations such as Markowitz’s investment formula. Using 40 years of U.S. stock market data to predict future returns, one study found that simply distributing money evenly among either 25 or 50 stocks usually yielded more money than 14 complex investment strategies, including Markowitz’s (SN Online: 5/20/11).

Unlike Markowitz’s procedure, dividing funds equally among diverse buys spreads out investment risks without mistaking accidental and random financial patterns in the past for good bets.

Gigerenzer and other investigators of powerful rules of thumb emphasize public education in statistical literacy and effective thinking strategies over nudging schemes. Intended effects of nudges are often weak and short-lived, they contend. Unintended effects can also occur, such as regrets over having accepted the standard investment rate in a company’s savings plan because it turns out to be too low for one’s retirement needs. “Nudging people without educating them means infantilizing the public,” Gigerenzer wrote in 2015.

Moved to do harm

As studies of irrational decision making took off around 50 years ago, so did a field of research with especially troubling implications. Social psychologists put volunteers into experimental situations that, in their view, exposed a human weakness for following the crowd and obeying authority. With memories of the Nazi campaign to exterminate Europe’s Jews still fresh, two such experiments became famous for showing the apparent ease with which people abide by heinous orders and abuse power.

First, Yale psychologist Stanley Milgram reported in 1963 that 65 percent of volunteers obeyed an experimenter’s demands to deliver what they thought were increasingly powerful and possibly lethal electric shocks to an unseen person — who was actually working with Milgram — as punishments for erring on word-recall tests. This widely publicized finding appeared to unveil a frightening willingness of average folks to carry out the commands of evil authorities (SN: 8/20/77, p. 117).

A disturbing follow-up to Milgram’s work was the 1971 Stanford Prison Experiment, which psychologist Philip Zimbardo halted after six days due to escalating chaos among participants. Male college students assigned to play guards in a simulated prison had increasingly abused mock prisoners, stripping them naked and denying them food. Student “prisoners” became withdrawn and depressed.

Zimbardo argued that extreme social situations, such as assuming the role of a prison guard, will overwhelm self-control. Even mild-mannered college kids can get harsh when clad in guards’ uniforms and turned loose on their imprisoned peers, he said.

Volunteers in Stanley Milgram’s obedience-to-authority experiments thought they were giving shocks to people who erred on a test, such as the seated man here, who was actually working with Milgram.© 1968 by S. Milgram, © Renewed 1993 by Alexandra Milgram. From The Film Obedience Distributed by Alexander Street Press

Volunteers in Stanley Milgram’s obedience-to-authority experiments thought they were giving shocks to people who erred on a test, such as the seated man here, who was actually working with Milgram.© 1968 by S. Milgram, © Renewed 1993 by Alexandra Milgram. From The Film Obedience Distributed by Alexander Street Press  When college students assumed the roles of guards (left) and prisoners (right) in the 1971 Stanford Prison Experiment, the group descended into chaos within a few days.P.G. Zimbardo

When college students assumed the roles of guards (left) and prisoners (right) in the 1971 Stanford Prison Experiment, the group descended into chaos within a few days.P.G. Zimbardo

Milgram’s and Zimbardo’s projects contained human drama and conflict that had widespread, and long-lasting, public appeal. A 1976 made-for-television movie based on Milgram’s experiment, titled The Tenth Level, starred William Shatner. A 2010 movie inspired by the Stanford Prison Experiment, simply called The Experiment, starred Academy Award winners Adrien Brody and Forest Whitaker.

Despite the lasting cultural impact of the obedience-to-authority and prison experiments, some researchers have questioned Milgram’s and Zimbardo’s conclusions. Milgram conducted 23 obedience experiments, although only one was publicized. Overall, volunteers usually delivered the harshest shocks when encouraged to identify with Milgram’s scientific mission to understand human behavior. No one followed the experimenter’s order, “You have no other choice, you must go on.”

Schools of thought

Researchers have taken a variety of often conflicting, sometimes complementary approaches to the study of human thought and behavior.

1899 — Freudian psychoanalysis: Study and treatment of unconscious mental conflicts

1912 — Gestalt psychology: Study of unified perceptions rather than their parts

1913 — John Watson’s behaviorism: Study of the prediction and control of human behavior

1938 — B.F. Skinner’s behaviorism: Study of behaviors conditioned by rewards and punishments

1956 — Cognitive revolution: Study of the mind using artificial intelligence and computers

1971 — Heuristics and biases (Kahneman and Tversky): Study of irrational, mistaken decisions

1999 — Ecological rationality (Gigerenzer): Study of how mental shortcuts work in the right settings

2010 — WEIRD/cross-cultural movement: Study of how people outside Western cultures think

Indeed, people who follow orders to harm others are most likely to do so because they identify with a collective cause that morally justifies their actions, argued psychologists S. Alexander Haslam of the University of Queensland and Stephen Reicher of the University of St. Andrews in Scotland 40 years after the famous obedience study. Rather than blindly following orders, Milgram’s volunteers cooperated with an experimenter when they viewed participation as scientifically important — even if, as many later told Milgram, they didn’t want to deliver shocks and felt bad after doing so.

Data from the 1994 ethnic genocide in the African nation of Rwanda supported that revised take on Milgram’s experiment (SN: 8/19/17, p. 22). In a 100-day span, members of Rwanda’s majority Hutu population killed roughly 800,000 ethnic Tutsis. Researchers who later examined Rwandan government data on genocide perpetrators estimated that only about 20 percent of Hutu men and a much smaller percentage of Hutu women seriously injured or killed at least one person during the bloody episode. Most Hutus rejected pressure from political and community leaders to join the slaughter.

Neither did Zimbardo’s prisoners and guards passively accept their assigned roles. Prisoners at first challenged and rebelled against guards. When prisoners learned from Zimbardo that they would have to forfeit any money they’d already earned if they left before the experiment ended, their solidarity plummeted, and the guards crushed their resistance. Still, a majority of guards refused to wield power tyrannically, favoring tough-but-fair or friendly tactics.

In a second prison experiment conducted by Haslam and Reicher in 2001, guards were allowed to develop their own prison rules rather than being told to make prisoners feel powerless, as Zimbardo had done. In a rapid chain of events, conflict broke out between one set of guards and prisoners who formed a communal group that shared power and another with guards and prisoners who wanted to institute authoritarian rule. Morale in the communal group sank rapidly. Haslam stopped the experiment after eight days. “It’s the breakdown of groups and resulting sense of powerlessness that creates the conditions under which tyranny can triumph,” Haslam concluded.

Milgram’s and Zimbardo’s experiments set the stage for further research alleging that people can’t control certain harmful attitudes and behaviors. A test of the speed with which individuals identify positive or negative words and images after being shown white and Black faces has become popular as a marker of unconscious racial bias. Some investigators regard that test as a window into hidden prejudice — and implicit bias training has become common in many workplaces. But other scientists have questioned whether it truly taps into underlying bigotry. Likewise, stereotype threat, the idea that people automatically act consistently with negative beliefs about their race, sex or other traits when subtly reminded of those stereotypes, has also attracted academic supporters and critics.

Diagnostic disarray

From 1952 to 1980, the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, or DSM, divided mental ailments into less-debilitating neuroses and more-debilitating psychoses. Other conditions were grouped under psychosomatic illnesses, personality disorders and brain or nervous system problems. Architects of an update published in 1980, DSM-III, wanted psychiatry to become a biological science, so they emphasized medications over psychotherapy for treating mental disorders.

In 2010, scientists dissatisfied with DSM’s often fuzzy, symptom-based definitions of mental disorders rebelled and tried to define mental conditions based on brain and behavioral measures. One such approach involves a still-preliminary measure of a susceptibility to mental illness in general, called a p score. This score is thought to reflect a person’s “internalizing” liability to develop anxiety and mood disorders, an “externalizing” liability, such as to abuse drugs and break laws, and a propensity to delusions and other forms of psychotic thinking. Researchers hope eventually to use p scores to evaluate how well psychotherapies and psychoactive medications treat and prevent mental disorders. — Bruce Bower

Improving lives and life spans

It has taken a public health crisis to stimulate a level of cooperation across disciplines within and even outside the social sciences rarely reached in the last century. After a long stretch of increasing longevity, life spans of Americans have declined in recent years, fueled by drug overdoses and other “deaths of despair” among poor and working-class people plagued by job losses and dim futures.

Economists, psychologists, psychiatrists, sociologists, epidemiologists and physicians have begun to explore potential reasons for recent longevity losses, with an eye toward stemming a rising tide of early deaths.

Two Princeton University economists, Anne Case and Angus Deaton, highlighted this disturbing trend in 2015. After combing through U.S. death statistics, Case and Deaton observed that mortality rose sharply among middle-aged, non-Hispanic white people starting in the late 1990s. In particular, white, working-class people ages 45 to 54 were increasingly drinking themselves to death with alcohol, succumbing to opioid overdoses and committing suicide.

Job losses that resulted as mining declined and manufacturing plants moved offshore, high health care costs, disintegrating families and other stresses rendered more people than ever susceptible to deaths of despair, the economists argued. A similar trend had stoked deaths among inner-city Black people in the 1970s and 1980s.

If Case and Deaton were right, then researchers urgently needed to find a way to measure despair (SN: 1/30/21, p. 16). Two big ideas guided their efforts. First, don’t assume depression or other diagnoses correspond to despair. Instead, treat despair as a downhearted state of mind. Tragic life circumstances beyond one’s control, from sudden unemployment to losses of loved ones felled by COVID-19, can trigger demoralization and grief that have nothing to do with preexisting depression or any other mental disorder.

Second, study people throughout their lives to untangle how despair develops and prompts early deaths. It’s reasonable to wonder, for instance, if opioid addiction more often afflicts young adults who have experienced despair since childhood, versus those who first faced despair in the previous year.

One preliminary despair scale consists of seven indicators of this condition, including feeling hopeless and helpless, feeling unloved and worrying often. This scale has shown promise as a way to identify those who are likely to think about or attempt suicide and to abuse opioids and other drugs.

Deaths of despair belong to a broader public health and economic crisis, concluded a 12-member National Academies of Sciences, Engineering and Medicine committee in 2021. Since the 1990s, drug overdoses, alcohol abuse, suicides and obesity-related conditions caused the deaths of nearly 6.7 million U.S. adults ages 25 to 64, the committee found. Whether obesity is rarely or often associated with despair is an open question.

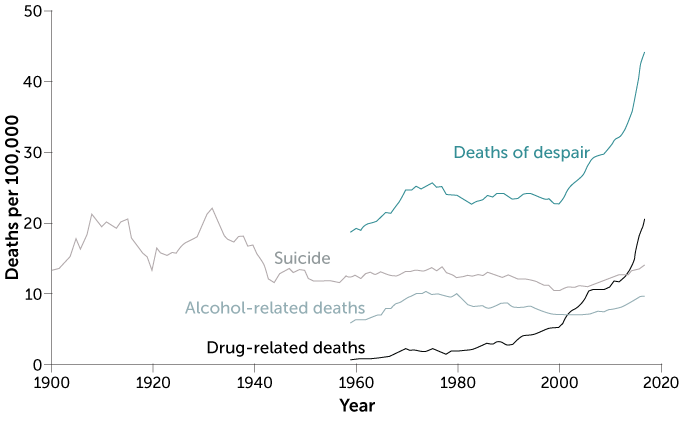

Self-harm

Social scientists are exploring reasons for rising numbers of “deaths of despair” in the United States, and the rising role played by drug overdoses, as compared with alcohol abuse and suicide.

U.S. deaths of despair, 1900–2017, age-adjusted  T. Tibbitts Source: U.S. Congress Joint Economic Committee 2019

T. Tibbitts Source: U.S. Congress Joint Economic Committee 2019

Deaths from those causes hit racial minorities and working-class people of all races especially hard from the start. The COVID-19 pandemic further inflamed that mortality trend because people with underlying health conditions were especially vulnerable to the virus.

Perhaps findings with such alarming public health implications can inform policies that go viral, in the best sense of that word. Obesity-prevention programs for young people, expanded drug abuse treatment and stopping the flow of illegal opioids into the United States would be a start.

Whatever the politicians decide, the science of us has come a long way from Watson and Rayner instilling ratty fears in an unsuspecting infant. If Little Albert were alive today, he might smile, no doubt warily, at researchers working to extinguish real-life anguish.

Trustworthy journalism comes at a price.

Scientists and journalists share a core belief in questioning, observing and verifying to reach the truth. Science News reports on crucial research and discovery across science disciplines. We need your financial support to make it happen – every contribution makes a difference.

Subscribe or Donate Now