Uranus’s upper atmosphere has been cooling for decades—and now scientists have shown why. Observations from Earth have shown Uranus’ upper atmosphere has been cooling for decades, with no clear explanation.

Now, a team led by Imperial College London scientists has determined that unpredictable long-term changes in the solar wind—the stream of particles and energy coming from the sun—are behind the drop.

The team predict Uranus’ upper atmosphere should continue to get colder or reverse the trend and become hotter again depending on how the solar wind changes over the coming years.

Lead researcher Dr. Adam Masters, from the Department of Physics at Imperial, said, “This apparently very strong control of Uranus’ upper atmosphere by the solar wind is unlike what we have seen at any other planet in our solar system.

“It does mean that planets outside the solar system could be in the same situation. These insights could therefore help researchers investigating exoplanets, by shedding light on the kinds of signals that might be detected coming from similar planets around distant stars.”

The research was published Nov. 14 in the journal Geophysical Research Letters.

A cool mystery

The last and only spacecraft to fly past Uranus was Voyager 2 in 1986, on its way out of the solar system. It was able to take the temperature of the upper part of Uranus’ atmosphere, called the thermosphere.

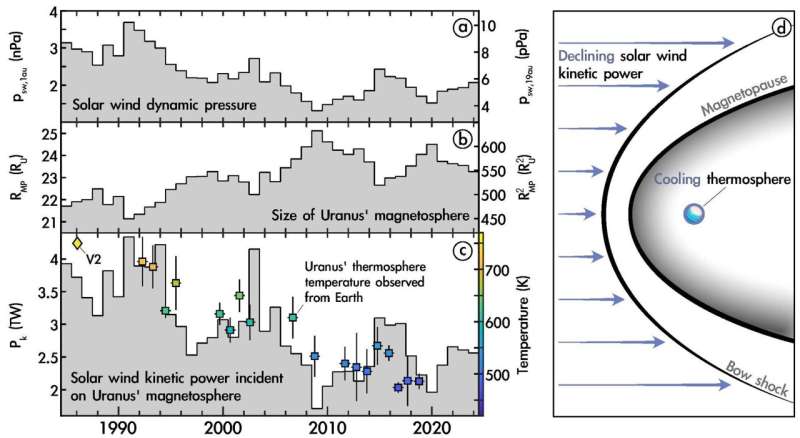

Since then, Earth-based telescopes have been able to measure the temperature of Uranus’ thermosphere regularly—and in that time, its overall temperature has approximately halved.

The Earth also has a thermosphere, but it has not experienced the same dramatic global temperature change, and neither have any other solar system planets with monitored thermospheres.

Scientists wondered if it could be due to the 11-year “solar cycle” of sunspot activity, but after 30 years of collecting data, no pattern was detected except the steady decline. A simple seasonal effect was also ruled out, since Uranus’ equinox came and went in 2007.

The mystery was finally solved when the paper’s authors, then working in slightly different fields, came together at a conference. They realized the explanation might be to do with the gradual changes in properties of the solar wind in the same time frame.

Changing influences

In Earth’s thermosphere, the temperature is predominantly controlled by sunlight—with the photons (light particles) bringing in energy and causing certain reactions. The intensity of these photons coming from the sun goes up and down with the 11-year solar cycle.

However, the solar wind flowing away from the sun into space has also been changing in a different way, over a longer time scale. The annual average outward pressure of the solar wind has been slowly but significantly dropping since around 1990, while showing little correlation to the 11-year cycle. This decline, however, closely mirrors Uranus’ thermosphere temperature decline.

This suggested to the team that Uranus’ thermosphere temperature is not controlled by photons, like the Earth’s. Instead, it appears the solar wind pressure decline has been making the typical size of Uranus’ protective magnetic “bubble” become bigger.

As this bubble, known as the magnetosphere, is an obstacle to the solar wind reaching the planet’s surface, a larger bubble means a larger obstacle. This drives energy flow through space around Uranus, ultimately reaching the planet’s thermosphere and appearing to strongly control its overall temperature.

The result suggests that for planets nearer their parent star—like the Earth is to the sun—their thermosphere is controlled by starlight. But for planets further out, which can have far larger magnetospheres, the incident energy from the stellar wind can be a much stronger factor.

Discover the latest in science, tech, and space with over 100,000 subscribers who rely on Phys.org for daily insights.

Sign up for our free newsletter and get updates on breakthroughs,

innovations, and research that matter—daily or weekly.

To Uranus—and beyond

Dr. Masters is part of an international team defining the science goals for a future NASA mission to Uranus, planned for launch in the 2030s. Uranus’ cooling thermosphere was a mystery to be solved, but with little idea of the possible cause, it had been tricky to come up with a theory the mission could test.

That has now changed, with this discovery both predicting how Uranus’ thermosphere should continue to evolve and overhauling this future mission science goal to focus on how solar wind energy actually gets into Uranus’ unusual magnetosphere. The team are also interested in whether there is a similar situation at Neptune, which also hasn’t been visited since Voyager in the 1980s.

In the meantime, the discovery could help with characterizing exoplanets. Wherever the situation is like that at Uranus, emissions from the exoplanet’s upper atmosphere—including auroras—should be highly sensitive to how the incident stellar wind is evolving. The team suggests observers should focus more on exoplanets further from their parent star and/or in systems with strong stellar winds, where emissions may have been underestimated so far.

Dr. Masters explained, “This strong star-planet interaction at Uranus could have implications for establishing if different exoplanets generate strong magnetic fields in their interiors—an important factor in the search for habitable worlds outside our solar system.”

The mystery of why the solar wind itself is changing however, with pressure declining over decades, is a question for other scientists.

More information:

A. Masters et al, Solar Wind Power Likely Governs Uranus’ Thermosphere Temperature, Geophysical Research Letters (2024). DOI: 10.1029/2024GL111623

Citation:

Solar wind power likely governs Uranus’ thermosphere temperature (2024, November 15)

retrieved 15 November 2024

from https://phys.org/news/2024-11-solar-power-uranus-thermosphere-temperature.html

This document is subject to copyright. Apart from any fair dealing for the purpose of private study or research, no

part may be reproduced without the written permission. The content is provided for information purposes only.