Over 300 years ago, Swiss physician Johannes Hofer observed disturbing behaviors among Swiss mercenaries fighting in far-flung lands. The soldiers were prone to anorexia, despondency and bouts of weeping. Many attempted suicide. Hofer determined that the mercenaries suffered from what he called “nostalgia,” which he concluded was “a cerebral disease of essentially demonic cause.”

Nowadays, nostalgia’s reputation is much improved. Social psychologists define the emotion — which Hofer saw as synonymous with “homesickness” — as a sentimental longing for meaningful events from one’s past. And research suggests that nostalgia can help people cope with dementia, grief and even the disorientation experienced by immigrants and refugees (SN: 3/1/21).

Nostalgia may even help people cope with the COVID-19 pandemic. In a study published September 8 in Social, Psychological and Personality Science, researchers found when some lonely, unhappy people reminisced about better, pre-pandemic moments, they felt happier. The results suggest that nostalgia can serve as an antidote to loneliness during the pandemic, the researchers conclude.

“A good analogy is the immune system,” says social psychologist Tim Wildschut of the University of Southampton in England. “A viral infection may make you ill, but it also activates your immune system and your immune system makes you better. Loneliness reduces happiness but also triggers nostalgia, and nostalgia increases happiness.”

In the new study, Wildschut and colleagues first surveyed over 3,700 participants in the United States, United Kingdom and China to assess people’s levels of loneliness, nostalgia and happiness during the early days of the pandemic. Surveys varied slightly by country, but for most questions or statements, participants responded on a scale from 1 to 7, with 1 for “not at all” and 7 for “very much.” For instance, participants in the United States rated how isolated they felt from the rest of the world in the week prior to the survey, how happy they felt compared with their peers and their overall feelings of nostalgia.

The researchers found that across the three countries, people who scored relatively high in loneliness also, not surprisingly, scored lower in happiness. But when the team drilled down on the role nostalgia plays, they found people who didn’t indulge in those memories were the least happy.

“Loneliness [triggers] unhappiness and nostalgia. Then unhappiness and nostalgia fight with each other,” says coauthor Constantine Sedikides, a social psychologist also at the University of Southampton.

Some 300 years ago, Swiss mercenaries in far-flung lands, such as the four men shown here in this 1778 engraving, suffered severe homesickness, characterized by weeping, anorexia and thoughts of self harm. Physician Johannes Hofer termed their affliction “nostalgia,” describing it as “a cerebral disease of essentially demonic cause.”Swiss National Museum

Some 300 years ago, Swiss mercenaries in far-flung lands, such as the four men shown here in this 1778 engraving, suffered severe homesickness, characterized by weeping, anorexia and thoughts of self harm. Physician Johannes Hofer termed their affliction “nostalgia,” describing it as “a cerebral disease of essentially demonic cause.”Swiss National Museum

Meanwhile, in three experiments with new sets of U.S. participants, the researchers manipulated people’s nostalgia levels, using the spring 2020 lockdown as a proxy for heightened loneliness. For example, in one experiment conducted in April 2020, the researchers recruited just over 200 online participants. The team induced nostalgia in half the participants by having them write four words describing a specific nostalgic event from their past. Participants were then prompted to write freely for three minutes about how that past experience made them feel. People in the control group completed the same tasks but about ordinary past experiences.

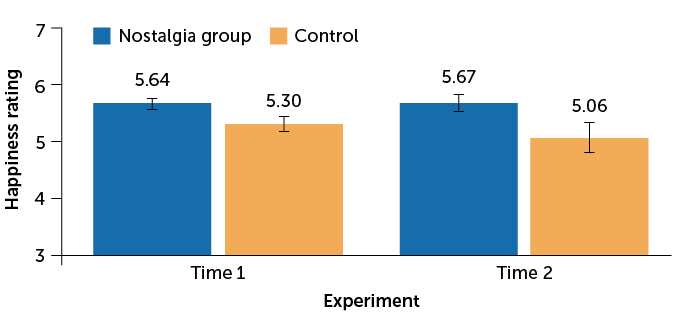

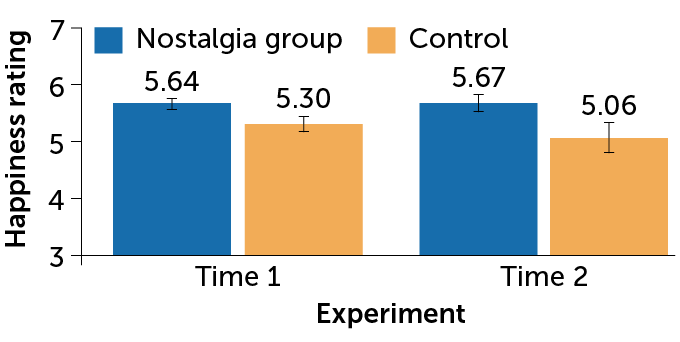

Those experiments revealed that, compared with the control group, participants in the nostalgia group reported slight but statistically significant higher happiness levels, as measured by the same 1-7 scale used in the earlier surveys. For instance, in the experiment with the 200-plus participants, the researchers found that happiness scores in the nostalgia group averaged 5.64 compared with 5.3 in the control group. Statistical analysis suggests that nostalgia can explain about 2 percent of the variation in happiness, the researchers say.

Those results may sound trivial, but even small variations can yield large results when viewed across large populations or across time, says personality psychologist Friedrich Götz of the University of British Columbia in Vancouver.

“Let’s say you are a happy person every day of your life. Chances are you will have a more fulfilled life than if you are a less happy person,” Götz says. “So 2 percent can make a difference because our happiness influences how we act, feel and think every day of our lives.”

Nostalgia booster

Early in the pandemic, researchers tested the impact of nostalgia on happiness. Volunteers were asked to call up a special memory and spend three minutes writing about it. When asked to rate their happiness on a scale of 1 to 7, this group scored slightly higher than volunteers in the control group who were asked to think about an ordinary memory (Time 1). A day or two after the original experiment, researchers asked participants in the nostalgia group to think about their memory again. That “nostalgia booster” once again prompted higher happiness scores (Time 2).

Testing a nostalgic versus ordinary memory’s effect on happiness  C. Chang

C. Chang  C. Chang Source: X. Zhou et al/Social, Psychological and Personality Science 2021

C. Chang Source: X. Zhou et al/Social, Psychological and Personality Science 2021

The hope that nostalgia-induced happiness could build up over time underpins some researchers’ long-term goal of harnessing and deploying techniques to trigger nostalgic memories as a form of therapy. Nostalgia can connect people to their past, present and even desired future selves, these researchers say. And since many nostalgic memories often involve other people, they can also help people feel linked to a wider community.

In one study, for example, existential psychologist Clay Routledge and colleagues tapped nostalgia’s social side. Participants first completed an established “nostalgia inventory,” where they rated on a scale from 1 to 5 how nostalgic they felt about 20 aspects of their past lives, such as family and vacations. The researchers then asked people about the types of studies that they might want to participate in later on. Two of those potential studies involved meeting other participants while two others did not.

Participants reporting high levels of nostalgia, especially those nostalgic for social experiences, were more likely than other participants to select the studies that involved meeting new people, the researchers reported in the December 2015 Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. That suggests that proneness to remembering meaningful past social experiences engenders future social experiences, the team says.

“Nostalgia isn’t just people remembering time with loved ones,” says Routledge, of North Dakota State University in Fargo. “It’s orienting them toward building new social experiences.”

A key question, though, is if nostalgia’s benefits can persist beyond that fleeting moment of remembrance. Wildschut’s team found that nostalgia’s benefits, in terms of happiness, faded after just a day or two. But nostalgia-induced happiness persisted for a couple days when the researchers reminded people to think about that special memory.

Crucially, nostalgia therapy may not be for everyone. Researchers reported in October 2019 in Personality and Individual Differences that invoking nostalgia in individuals who viewed relationships as a source of comfort and security increased those people’s intention to engage with others. The reverse, however, held true for individuals who saw relationships as a source of pain.

“For these types of avoidant people … nostalgia pushed them in the opposite direction. They were even less likely to want to connect with others on a deeper level,” says existential and social psychologist Andrew Abeyta of Rutgers University–Camden in New Jersey.

Sign Up For the Latest from Science News

Headlines and summaries of the latest Science News articles, delivered to your inbox

Client key* E-mail Address* Go

Thank you for signing up!

There was a problem signing you up.

Wildschut and colleagues found a similar result when investigating whether invoking nostalgia among Syrian refugees living in Saudi Arabia could increase self-esteem, sense of meaning in life, feelings of social belonging and optimism.

In that study, refugees in an experimental group wrote about meaningful events from their past, while refugees in a control group wrote about ordinary events. The experiment showed that triggering nostalgia in refugees high in resilience — a trait defined by a capacity to withstand and recover from adversity — resulted in more positive emotions than those reported by resilient refugees in a control group, the team concluded in the December 2019 European Journal of Social Psychology. But while inducing nostalgia in refugees low in resilience did help them feel a greater sense of continuity in life and more socially connected compared with a low-resilience control group, nostalgic memories also made them feel less optimistic about the future.

“When you push the test of nostalgia to those extremes, it’s a very, very tough test,” Wildschut says.

Caveats aside, Wildschut remains optimistic about developing some form of nostalgia therapy. He recalls a conversation with his young daughter many years ago. When he asked her how long nostalgia lasts, she replied “forever,” Wildschut says. “What she meant is that the memory is there, and you can recall it any time.” Ultimately, he and other nostalgia researchers hope to one day identify suitable candidates for nostalgia therapy and then train those people to recall special memories whenever they feel blue.