Not far from the hallowed spires and research labs of Oxford University, two workers in overalls and hard hats are searching for air travel’s “holy grail” – climate-friendly airline fuel made from nothing but carbon dioxide and green hydrogen.

That is how OXCCU chair Alan Aubrey describes the Oxford-based company’s mission to scale up its nascent production of so-called e-SAF, a synthetic hydrocarbon fuel that backers hope could one day become a viable, green alternative to traditional kerosene jet fuel.

“The beauty of this is that the inputs – CO2 and hydrogen – are at least theoretically unlimited,” the company’s CEO Andrew Symes told reporters during a visit to OXCCU’s experimental plant last year. “This industry – yes it starts small – but it can grow and scale and become very big.”

E-SAF can reduce planet-heating carbon emissions by up to 90% compared to conventional jet fuels. In contrast to more established forms of SAF, e-SAF does not require vast quantities of raw materials such as used cooking oil (UCO) or – more controversially – agricultural products such as sugar-based ethanol, soy or palm oil.

It is easy to see the fledgling industry’s appeal as airlines and governments fret over how to tackle air travel’s growing carbon emissions. They are closely watching the progress of startups such as OXCCU, whose backers include United Airlines, Saudi energy giant Aramco and Italy’s Eni.

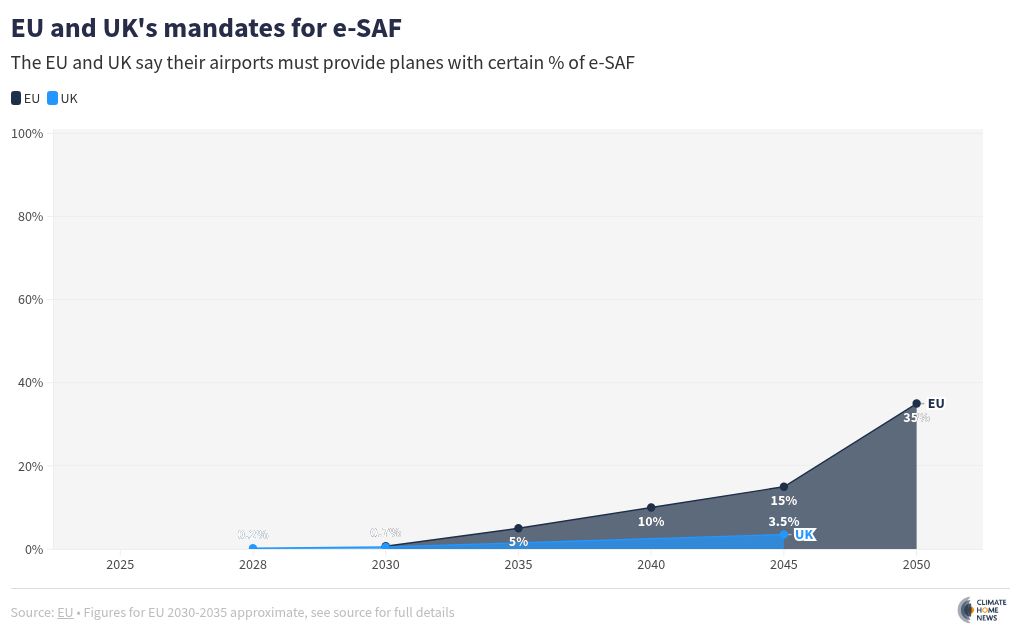

Policymakers in the European Union and the UK are also taking note, and fuel providers are being mandated to supply growing amounts of e-SAF, starting with 0.2% in the UK in 2028 and 0.7% in the EU in 2030.

So far, e-SAF has only been used for a few high-profile test flights. In 2021, Dutch airline KLM used 5% SAF on a flight from Amsterdam to Madrid, and the British air force was the first to power a plane entirely on e-SAF when a two-seater made a short trip around a private airport.

But scaling up synthetic fuel production could be a long haul.

To fly or not to fly?

E-SAF remains prohibitively expensive to produce and so far its use has mainly been limited to demonstration projects, like OXCCU’s plant at Oxford Airport. Critics say it could be decades away from becoming commercially viable.

Producing green hydrogen from water to make the fuel requires huge amounts of renewable electricity, which the industry’s detractors say is a waste of scarce green power resources.

Such obstacles, they say, make it a distraction from the most obvious solution to aviation emissions: flying less.

Aviation’s Green Dream: Read our investigative series on Sustainable Aviation Fuel

“The idea that we can magic up this gigantic renewable capacity to produce e-fuel … it’s just not doable, it’s not going to be affordable, and it makes no sense from the perspective of using resources,” said Alethea Warrington, a campaigner on aviation issues at Possible, a UK-based NGO that promotes climate action.

Some climate campaigners are more positive about e-SAF. Aoife O’Leary, head of climate think-tank Opportunity Green, said there is a need to “deal with the unsustainable growth of aviation”, but that we should “also decarbonise the flights that exist”.

Acknowledging the huge renewable energy requirements needed to make green hydrogen, she said that “if paid for by the industry, then it would be additional to the renewable energy that exists otherwise”.

Aviation industry body IATA, the International Air Transport Association, urged governments in a recent statement to redirect into renewables “a portion of the $1 trillion in subsidies that governments globally grant for fossil fuel” and to develop policies“ to ensure SAF is allocated an appropriate portion of renewable energy production”.

The Possible group has called instead for measures to limit flight numbers, for example, a frequent flyer tax and efforts to promote rail transport.

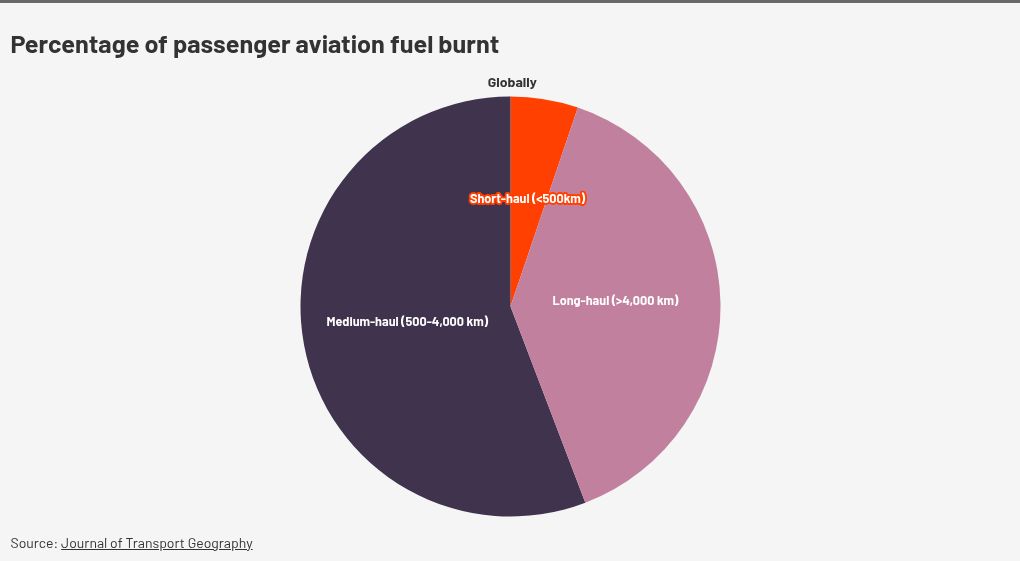

But sweeping policies to reduce flying would be unpalatable for many governments and painful for passengers. Surveys from Europe and the US suggest that about a quarter of flights are taken to visit friends and relatives, and globally about 95% of flights are longer than 500 km (310 miles) – making other forms of transport less practical.

In the meantime, the world’s appetite for flying continues to grow, spurring efforts to find a way to tackle the carbon footprint of aviation – today the cause of about 2.5% of all energy-related emissions.

On its current trajectory, the aviation industry is on course to blow a big hole in the world’s goal to limit global warming to 1.5 degrees Celsius. According to the International Civil Aviation Organization, a UN agency, the sector’s emissions could double or even triple between 2015 and 2050.

That is partly because other sectors, such as road transport and power generation, are cutting their emissions by switching to renewable electric energy – still a distant technological prospect for commercial aircraft.

Fuel from air and water

Concern that plant-based SAF could increase competition for land and raise deforestation risks might boost efforts to ramp up e-SAF production.

New rules in the EU and the UK say only waste products such as UCO should be used to make SAF, but experts and industry insiders told an investigation by Climate Home News and its partner The Straits Times that in key UCO supplier Malaysia, unused or barely used palm oil is being passed off as waste oil.

In contrast, synthetic fuel is made by passing an electric current – produced with renewable electricity – through water, splitting it into hydrogen and oxygen gas. The oxygen is released harmlessly into the atmosphere, while the hydrogen is captured and mixed with carbon dioxide (CO2) to make the hydrocarbon jet fuel.

E-SAF producers such as OXCCU and US-based Twelve, which is set to supply Alaska Airlines and International Airlines Group, source their CO2 from industries that produce it as a waste product.

“It’s essentially getting two uses out of the carbon before it goes up into the atmosphere,” Symes said, adding that an even better option would be using technology to capture CO2 directly from the air, which would be fully circular and carbon neutral.

While OXCCU buys its green hydrogen, Twelve is planning to make its own at its factory in the US Pacific Northwest. “That’s something we’ve invested a lot of time and money into over the past few years,” the company’s vice president of business development Ashwin Jadhav told Climate Home.

Green hydrogen challenge

Scaling up green hydrogen production will be a “real challenge”, despite e-SAF’s “immense” potential, said Azim Norazmi, climate policy manager at IATA.

With the global aviation industry’s net-zero goal just 25 years away, he said plant-based biofuels – not e-SAF – will be the “biggest contributor” to meeting that target.

Aurelia Leeuw, Opportunity Green’s EU policy director, said one of the issues holding back e-SAF production is that airlines generally only want short-term contracts of around a year, while producers need longer-term certainty to justify investments in ramping up output.

The European Commission is expected to announce a sustainable aviation plan in the next few months. Leeuw and others are hoping this will help solve the problem by bringing international aviation into the EU’s Emissions Trading System (ETS) and using the funds raised from imposing charges on airlines to buy large quantities of e-SAF. An intermediary – such as the European Commission – would then sell the fuel on short-term contracts.

The idea under consideration would bring flights taking off in Europe that land outside the continent into the ETS, generating more funding from the aviation industry to support investment in e-SAF.

Leeuw said demand for e-SAF is also being held back by airlines and fuel suppliers assuming that the European Commission will water down its mandates and not fully apply penalties for fuel suppliers that do not meet them. The size of these penalties will depend on the price difference between conventional jet fuel, SAF and e-SAF – but are likely to be thousands of dollars per tonne, according to Brussels-based NGO Transport & Environment.

“The European Commission is saying the [e-SAF] targets are not up for debate. But the airlines and oil and gas incumbents are lobbying them hard and playing off the uncertainty that they themselves are creating,” she said.

“There must be no doubt that these… are the targets – and those are the penalties,” she added.

This article was developed with the support of Journalismfund Europe.