Data won’t be confirmed until 2025 and developing countries say the rich world must make up for earlier shortfalls from the target

There will be no confirmation that rich countries have met their $100 billion a year climate finance promise until 2025 at the earliest.

That’s according to ministers from Canada and Germany, the two nations tasked with drawing up the “delivery plan” for belatedly meeting the pledge.

In an open letter, Canada’s Steven Guilbeault and Germany’s Jennifer Morgan, said on Friday that they were “confident that the goal will be met this year”.

That would be three years after the target date of 2020, as promised by wealthy nations at climate talks in 2009.

But, the ministers warned, “data on climate finance delivered in 2023 will not be available until 2025 due to data requirements and reporting processes in place”.

Climate finance failed to reach $100bn in 2020 (Photo: OECD)

Negotiators, campaigners and experts said the delay would damage trust between climate negotiators and questioned the legitimacy of rich countries climate finance figures.

Richard Klein is a senior research fellow at the Stockholm Environment Institute. He said developed countries were being “very naive if they think they can get away with this”.

He added that trust between governments is already very low and this will only confirm what developing countries criticise and undermine developed countries’ negotiating positions.

“You can’t have [German leader Olaf] Scholz going to G20 saying that he expects climate action of all partners, and then do this,” he said.

‘Too little, too late’

Alpha Kaloga is the African Group’s lead negotiator on finance and loss and damage. He told Climate Home that “we welcome the effort”, but even if $100 billion was provided in 2023, there would still be shortfalls to make up for in 2020, 2021 and 2022.

“The confidence shown by developed [countries] in term of fulfillment of the pledge does not match our understanding of the pledge,” he said.

Saleemul Huq, a Bangladeshi campaigner and adviser to the Cop28 presidency, told Climate Home that “the fact that developed countries still cannot guarantee the delivery of the mythical $100bn… is simply the symptom of their lack of seriousness to deliver on their promises”.

Climate Action Network campaigner Harjeet Singh said even if the target was met it was “too little and too late”, as the “genuine costs faced by developing nations run into trillions annually”

Player and referee

Since 2015, rich countries have tasked the Organisation for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD) with collecting this data.

Kaloga said this process is “not transparent as it seems that [developed countries] are player and referee at the same time”. The OECD is funded by its member countries, which are mostly developed nations.

Kaloga also said that the OECD’s classification of climate finance was “debatable” as reports by Oxfam and others have “revealed that much of the reported amount is overestimated”.

Oxfam said in June that the real value of rich countries climate finance in 2020 was just $24.5 billion. They got the official $83 billion figure by overstating climate benefits and taking loans at their face value, Oxfam said.

“If developed countries are serious about the statement, they should set an inclusive task force to track and estimate the support provided and received,” Kaloga said.

Reporting delays

The OECD’s figures are published about 18 months after the relevant year’s end.

Joe Thwaites, a senior advocate at the Natural Resources Defense Council, said that the delay is caused by some developed countries being “very slow in reporting their data”.

“EU member states report their climate finance for a given year less than a year later, so it’s clearly possible,” he added.

The delay means governments will go into Cop28 and Cop29 without assurance that the goal has been met, doing nothing to ease tensions between developed and developing countries.

Developing countries have criticised rich nations’ failure to meet the target. Cop28 president Sultan Al-Jaber said the “dismal failure” had been “holding up” progress in the negotiations.

Governments are now negotiating a post-2025 climate finance goal to succeed the $100 billion target. This new target is scheduled to be finalised in 2024.

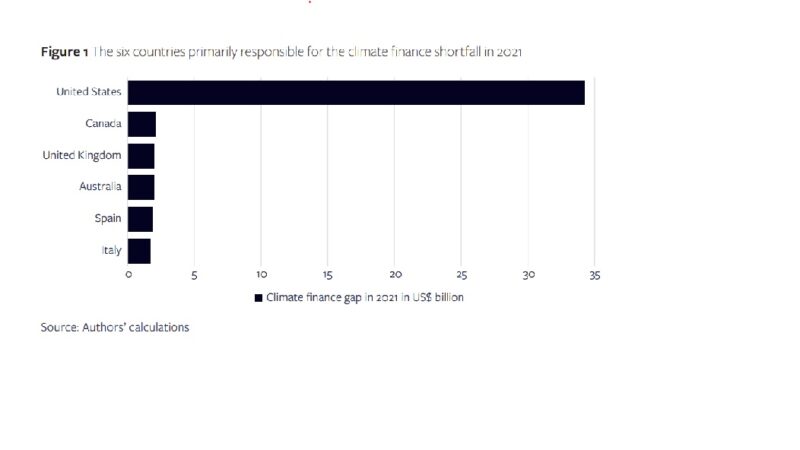

The US is responsible for the vast majority of the shortfall (Photo credit: ODI)

Previous promises

Rich nations have expressed similar confidence at meeting the target before.

In 2016, the UK and Australia had a similar role to that which Germany and Canada have now.

In their 2016 “roadmap”, they said they were “confident” it would be met by 2020 but in reality rich nations mobilised just $83.3 billion that year.

The OECD is expected to release figures for 2021 before Cop28 in November, which is not expected to narrow the gap to $100 billion completely.

According to research from the ODI think tank, the US is responsible for the vast majority of the shortfall to $100 billion.