Obstetrician Cynthia Gyamfi-Bannerman was treating patients in New York City when the COVID-19 pandemic swept in. Hospitals began filling up. Some of her pregnant patients were among the sick.

It was a terrifying time. Little was known about the virus called SARS-CoV-2 to begin with, much less how it might affect a pregnancy, so doctors had to make tough calls. Gyamfi-Bannerman remembers doctors getting waivers to administer the antiviral drug remdesivir to pregnant COVID-19 patients, for instance, even though the drug hadn’t been tested during pregnancy.

“Our goal is to help the mom,” she says. “If we had something that might save her life — or she might die — we were 100 percent using all of those medications.”

These life-or-death decisions were very familiar to obstetricians even before the pandemic. Pregnant women have long been excluded from most drug testing to avoid risk to the fetus. As a result, there’s little data on whether many medications are safe to take while pregnant. This means tough choices for the roughly 80 percent of women who will take at least one medication during pregnancy. Some have serious conditions that can be dangerous for both mother and fetus if left untreated, like high blood pressure or diabetes.

“Pregnant women are essentially like everybody else,” Gyamfi-Bannerman says. They have the same underlying conditions, requiring the same drugs. In a 2013 study, the top 20 prescriptions taken during the first trimester included antibiotics, asthma and allergy drugs, metformin for diabetes, and antidepressants. Yet even for common drugs, the only advice available if you’re pregnant is “talk to your doctor.” With no data, doctors don’t have the answers either.

Obstetrician Cynthia Gyamfi-Bannerman (left) has conducted clinical trials to learn the effects of medications taken during pregnancy and advocates for more research involving pregnant people.Kyle Dykes/UC San Diego Health

Obstetrician Cynthia Gyamfi-Bannerman (left) has conducted clinical trials to learn the effects of medications taken during pregnancy and advocates for more research involving pregnant people.Kyle Dykes/UC San Diego Health

What’s frustrating to many doctors and researchers is that this lack of information is by design. Even the later stages of most clinical trials, which test a new drug’s safety and efficacy in people, specifically exclude pregnant people to avoid risk to the fetus. But in the wake of a pandemic that disproportionately harmed the pregnant population, researchers are questioning more than ever whether this is the best approach.

Typically, researchers have to justify excluding certain groups, such as older adults, from clinical trials in which they might benefit. “You never have to justify why you’re excluding pregnant people,” says Gyamfi-Bannerman, who now heads the obstetrics, gynecology and reproductive science department at the University of California, San Diego. “You can just go ahead and exclude them.

“The exclusion of pregnant people in clinical trials is a huge, historic problem,” she says, “and it really came to light with COVID.”

Pregnant in a crisis

Teresa Mathews was 43 years old when she found out she was pregnant in June 2020, just as the pandemic was tearing across the United States. “I was really worried,” she says. In addition to her age as a risk factor, Mathews has sickle cell trait, meaning she carries one defective gene copy that makes her prone to anemia and shortness of breath. COVID-19 also causes shortness of breath, so Mathews feared her unborn child could starve for oxygen if she caught the virus.

What’s more, the baby would be her first. “I don’t want to say it melodramatically, but it was my last chance of having a baby, right? So I didn’t really want to take chances.” She went into full lockdown for the rest of her pregnancy.

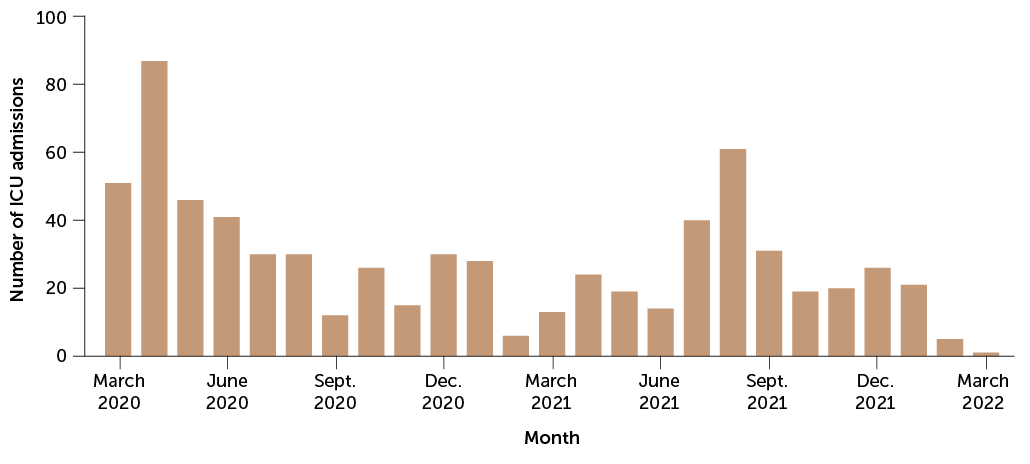

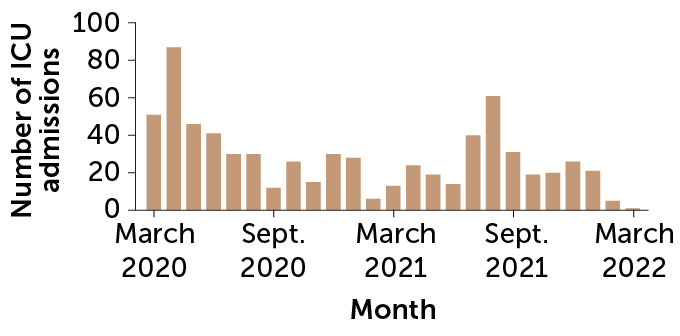

For good reason. A study during the pandemic’s first year in England found that pregnant women who got the virus were about twice as likely to have a stillbirth or early birth. And the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention reported in November 2020 that pregnant women are about three times as likely as other women to land in intensive care with COVID-19, and 70 percent more likely to die from the infection (SN Online: 2/7/22).

Heightened risk

Shown are admissions to hospital intensive care units during the pandemic. Unvaccinated pregnant women are about three times as likely as pregnant women who’ve been vaccinated to require intensive care for COVID-19.

Intensive care unit admissions among U.S. pregnant women with COVID-19, March 2020–March 2022  C. Chang

C. Chang  SOURCE: CDC

SOURCE: CDC

So when the race for a vaccine began, many doctors and officials hoped that vaccines would be tested in pregnant women and shown to be safe. There were promising signs: The U.S. Food and Drug Administration encouraged vaccine developers to include pregnant women in their trials. A large body of previous research suggested that risks would be low for vaccines like those for COVID-19, which do not contain live viruses.

But ultimately the three vaccines that the FDA cleared for use in the United States, from Pfizer/BioNTech, Moderna and Johnson & Johnson, excluded pregnant people from their initial clinical trials. After its vaccine was authorized for emergency use in December 2020, Pfizer began enrolling pregnant women for a clinical trial but called it off when federal officials recommended that all pregnant women get vaccinated. The company cited challenges with enrolling enough women for the trial, as well as ethical considerations in giving a placebo to pregnant individuals once the vaccine was recommended.

When pregnant people were excluded from vaccine trials, doctors knew it would be difficult to convince pregnant patients to take a vaccine that hadn’t been tested during pregnancy.

Mathews says she would have been willing to get vaccinated while pregnant if there had been data to support the decision. But the choice was made for her. Her daughter, Eulalia, was born healthy in February 2021, shortly before the vaccines became available to all adults in Mathews’ hometown of Knoxville, Tenn. At that point, there was still no clear guidance on whether to get vaccinated while pregnant or nursing.

Sign Up For the Latest from Science News

Headlines and summaries of the latest Science News articles, delivered to your inbox

Client key* E-mail Address* Go

Thank you for signing up!

There was a problem signing you up.

Officials at the National Institutes of Health in Bethesda, Md., were worried about that lack of direction. Diana Bianchi, director of the National Institute of Child Health and Human Development, called for more COVID-19 vaccine research in the pregnant population in a February 2021 commentary in JAMA. She wrote, “Pregnant people and their clinicians must make real-time decisions based on little or no scientific evidence.”

Meanwhile, social media and pregnancy websites filled the void with conspiracy theories and scary stories about vaccines causing infertility or miscarriages. Alarmed, the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists warned last October that “the spread of misinformation and mistrust in doctors and science is contributing to staggeringly low vaccination rates among pregnant people.”

Indeed, the CDC had issued an urgent health advisory the month before warning that only 31 percent of pregnant people were fully vaccinated, compared with about 56 percent of the general population. (CDC and many experts favor “pregnant people” as a general term. Science News is following the language used by sources, and refers to pregnant women when a study population was designated as such.)

“Every week, I look at the number of pregnant people who have died due to COVID. Right now, the most recent statistic is 257 deaths,” Bianchi said in January. “I look at that and I say, that was a preventable statistic.”

After the vaccines received emergency use authorization, the CDC analyzed the outcomes for nearly 2,500 vaccinated pregnant people and found no safety concerns related to pregnancy. The agency recommended vaccination for anyone who is pregnant, lactating or considering becoming pregnant. But that recommendation arrived more than six months after the first vaccine became available.

31,211

Number of U.S. pregnant women hospitalized with COVID-19, January 2020–March 2022

SOURCE: CDC

Since then, the vaccines have also proved to be highly effective in pregnancy. More than 98 percent of COVID-19 critical care admissions in a group of more than 130,000 pregnant women in Scotland were unvaccinated, researchers reported in January in Nature Medicine. And all of the infants who died had unvaccinated moms.

“The story of COVID is yet another cautionary tale,” says Anne Lyerly, a bioethicist at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill who trained as an obstetrician and gynecologist. “It highlighted what we’re up against.” Researchers have an ethical duty, she says, not only to protect fetuses from the potential risks of research, but also to ensure that “the drugs that go on the market are safe and effective for all the people who will take them.”

Good intentions

Increasingly, scientists are questioning what Gyamfi-Bannerman calls a “knee-jerk” tendency to exclude pregnant individuals from clinical trials. In 2009, Lyerly and colleagues formed the Second Wave Initiative to promote ethical ways to include pregnant women in research. As their ideas have spread, more researchers — mostly women — have held conferences and spearheaded research. Collectively, they’re pushing back on the prevailing culture “that pregnant people need to be protected from research instead of protected through research,” Bianchi says.

“We got here with good intentions,” says Brookie Best, a clinical pharmacologist at UC San Diego who studies medication use among pregnant people. “There were some terrible, terrible tragedies of pregnant people taking a drug and having bad outcomes.”

The most famous of these was thalidomide. Starting in the late 1950s, the drug was prescribed for morning sickness, but it had never been tested in pregnant people. By the early 1960s, it became clear that it caused birth defects including missing or malformed limbs (SN: 7/14/62, p. 22). Afterward, drug companies were reluctant to take on the risk, or legal liability, of potential birth defects. While the FDA enacted new safety rules in response to the thalidomide disaster, the agency did not require testing during pregnancy before drugs went to market.

In 1977, the FDA recommended the exclusion of all women of childbearing age from the first two phases of clinical trials. When the U.S. Congress passed a bill in 1993 requiring that women and minorities be included in clinical research, the requirement did not extend to pregnant women.

In the late 1950s and early 1960s, the drug thalidomide was prescribed to pregnant women for morning sickness without adequate testing. The drug resulted in birth defects, such as limb malformations, in thousands of children.Paul Fievez/BIPs/Getty Images

In the late 1950s and early 1960s, the drug thalidomide was prescribed to pregnant women for morning sickness without adequate testing. The drug resulted in birth defects, such as limb malformations, in thousands of children.Paul Fievez/BIPs/Getty Images

Some scientists still see plenty of good reasons not to include pregnant women in clinical trials. For example, reproductive epidemiologist Shanna Swan has seen unexpected health effects crop up long after substances were deemed safe. With that in mind, Swan, of the Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai in New York City, says that observational studies that follow women and their children after a drug has been approved remain the best approach. These studies are “expensive, and very slow,” she admits, but safer.

For decades, that level of precaution has extended to essentially all medications. As a result, the reproductive effects of a medicine aren’t usually discovered until long after a drug enters the market. Even then, such research is not required for most new drugs, so doctors and researchers must take the initiative. Typically, this happens through pregnancy registries, which enroll pregnant volunteers who are taking a particular drug and follow them throughout pregnancy or beyond.

But voluntary registries leave huge data gaps. A 2011 review of 172 drugs approved by the FDA in the preceding decade found that the risk of harm to fetal development was “undetermined” for 98 percent of them, and for 73 percent there was no safety data during pregnancy at all.

That doesn’t mean all those drugs are dangerous. Relatively few drugs cause major birth defects, and many of those fall into known classes. For example, ACE inhibitors used to control blood pressure have been linked to a range of issues, including kidney and cardiovascular problems in infants, when taken during pregnancy. But the potential for more subtle, long-term effects has been trickier to tease out.

For instance, several studies in the 2010s reported links between mothers taking antidepressants during pregnancy and their kids having developmental problems like attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder and autism spectrum disorder. Some moms became afraid to treat their own depression. But in 2017, studies of siblings found no difference in these conditions among children who had been exposed to antidepressants in the womb and those who had not (SN: 5/13/17, p. 9). More likely, the problem was the depression the mom was experiencing, the studies suggested, not the drugs.

No legal requirement

How the contents of a pregnant woman’s medicine cabinet might affect her child depends on a host of factors, including how the drug works and whether it crosses the placenta. The main way to gauge whether a drug may harm a fetus is through animal studies called developmental and reproductive toxicology, or DART, studies. But drug companies often don’t begin these studies until they’ve already gotten clinical trials rolling.

This creates a catch-22, because clinical trials can’t include pregnant people until DART studies suggest it’s safe to do so. That’s why Lyerly and others pushing for change say that pharmaceutical companies should start doing these studies earlier, before clinical trials begin.

In 2018, the FDA issued draft guidance to help the pharmaceutical industry decide how and when to include pregnant people in clinical trials (SN Online: 5/30/18). That guidance is an encouraging first step, Lyerly says, but it didn’t change any of the stringent rules for when pregnant people could be included in research.

Plus, it’s all completely voluntary, says Leyla Sahin, acting deputy director for safety in FDA’s Division of Pediatric and Maternal Health. “We advise industry…. We tell them we recommend that you include pregnant women in your clinical trials,” Sahin says. “But there’s no requirement.”

In fact, the FDA doesn’t even have the legal authority to create a requirement. In that sense, Sahin says, “we’re where pediatrics was 20 years ago.” Until Congress passed the Pediatric Research Equity Act of 2003, children were routinely excluded from clinical trials just as pregnant women are now. The pediatric law required drug companies to gather data on the safety and effectiveness of medications in children and to provide FDA an appropriate plan for pediatric studies.

Congress could pass a similar law for pregnancy. And in 2020, a government task force recommended exactly that to the Department of Health and Human Services, which oversees FDA. But “it’s almost like it’s gone into this black hole,” Sahin says. “We haven’t heard from HHS. We haven’t heard from Congress.”

Too few drugs have pregnancy safety data

Efforts to protect pregnant people and fetuses have resulted in very little safety information available for them and their doctors.

80

percent

Proportion of U.S. pregnant people who take at least one medication during pregnancy

Source: A.A. Mitchell et al/Am. J. Obstet. Gynecol. 2011

98

percent

Proportion of drugs approved by the FDA from 2000–2010 without data on fetal safety

Source: M.P. Adams, J.E. Polifka and J.M. Friedman et al/Am. J. Med. Genetics 2011

Stocking the medicine cabinet

Until clinical trials during pregnancy become more routine, pregnant people face an untenable choice — take a drug without knowing its safety, or leave their medical conditions untreated.

Case in point: A group of 91 doctors and scientists published a consensus statement in September 2021 in Nature Reviews Endocrinology warning that acetaminophen, the most commonly used drug during pregnancy, may harm fetal development. Research suggests the drug disrupts hormones, with effects ranging from undescended testicles in male infants to an increased risk of ADHD and autism spectrum disorder in boys and girls.

But as is often the case with drugs and pregnancy, there’s not exactly a consensus among doctors about what pregnant people should do. In response to the new paper, the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists issued a statement saying the evidence wasn’t strong enough to suggest doctors should change their standard practice, which is to recommend acetaminophen be taken as needed and in moderation.

Acetaminophen is an active ingredient in more than 600 medications, including Tylenol, and is estimated to be used by up to 65 percent of pregnant people in the United States. It has long been the preferred pain medication and fever reducer during pregnancy because the FDA recommends against the anti-inflammatory drugs known as NSAIDs — such as ibuprofen and aspirin — in the second half of pregnancy. Those drugs have been linked to rare fetal kidney problems and low amniotic fluid levels.

While at the University of Copenhagen, clinical pharmacologist David Kristensen began studying acetaminophen’s effects on fetal development after noticing that the drug is structurally similar to chemicals that disrupt hormones. In 2011, he and colleagues published animal and human studies linking acetaminophen use during pregnancy with concerning effects in infants, including undescended testicles.

“My ears perked up when I heard that,” says Swan, the Mount Sinai reproductive epidemiologist and coauthor of the 2021 acetaminophen review. She had seen similar effects with maternal exposure to phthalates, chemicals used in plastics that are known to alter the activity of hormones needed to regulate fetal development.

She and colleagues surveyed 25 years of acetaminophen studies. The group found that five out of 11 relevant studies linked prenatal acetaminophen use to urogenital and reproductive tract abnormalities in children, and 26 out of 29 epidemiological studies linked fetal exposure to acetaminophen with neurodevelopmental and behavioral problems. The strength of these links varied, but were “generally modest,” the authors wrote.

“We’re looking at subtle effects here,” Swan says, “but that doesn’t mean that they’re not important.” With such widespread use, “there’s a good chance that a fair number of offspring are affected.”

Although Swan is wary of testing new drugs in pregnant women, she would like to see better research on medications during pregnancy. “There’s a whole range of options short of doing human study,” she says.

To start with, Swan says, scientists need better data on what medications pregnant women are taking, and how much. That means more studies should ask women to keep daily logs of every pill they take. Researchers can also do more studies of drugs’ reproductive effects in animals, she notes, and even transplant human tissues such as brain, liver or gonads into animals to learn how they respond to drugs.

Not the same vulnerability

The cultural shift around pregnancy research may be gaining momentum.

Government-funded research is one key area for change. In 2016, the 21st Century Cures Act established an interagency task force on research specific to pregnant and lactating women. It included officials from NIH, CDC and FDA, as well as medical societies and industry. One of the task force’s recommendations was acted upon in 2018: removing pregnant women as a “vulnerable” group in a federal regulation called the Common Rule, which governs federally funded research. Pregnant women had been listed along with children, prisoners and people with intellectual disabilities as vulnerable and thus requiring special protections if included in research.

Unlike the other groups in that list, pregnant people “don’t have a diminished capacity to provide informed consent,” says Lyerly, the bioethicist at the University of North Carolina. That rule change alone could help “change the culture of research.”

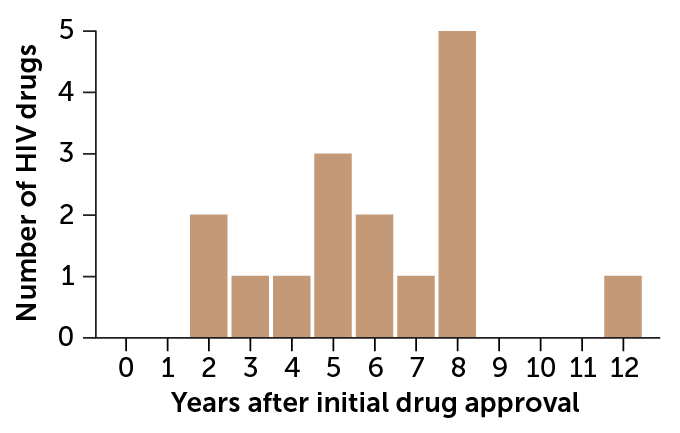

Meanwhile, researchers are forging ahead with studies on many drugs used during pregnancy. HIV drugs are among the most studied, says Best of UC San Diego, in part because the virus can pass from pregnant women to their fetuses. “So right off the bat, everybody knew that we needed to treat these [pregnant] patients with medication,” she says. Yet data on HIV drugs during pregnancy lagged as much as 12 years after FDA approval.

Waiting game

Even for HIV drugs, which are better studied during pregnancy than most drugs, it took an average of six years after U.S. Food and Drug Administration approval before the first data were published on a drug’s activity during pregnancy.

Lag between FDA approval and when data became available on HIV drug activity in pregnancy C. ChangC. Chang Source: A. Colbers et al/Clinical Infectious Diseases 2019

C. ChangC. Chang Source: A. Colbers et al/Clinical Infectious Diseases 2019

Many pregnant women appear to be willing to participate in research. More than 18,000 pregnant people had enrolled in the COVID-19 vaccine pregnancy registry as of March, and every year many volunteer for other pregnancy registries.

Gyamfi-Bannerman says that in her experience, plenty of pregnant patients are willing to volunteer, even for experimental drugs, if there’s potential to benefit from the drug and they will be monitored closely. At Columbia University, she helped lead a clinical trials network called the Maternal Fetal Medicine Units Network that specifically studies complications during pregnancy. “It’s a very safe and protective environment,” she says.

As for next steps, a few policy changes could make a big difference, Best says, like “getting those preclinical studies done earlier and allowing people who accidentally get pregnant while participating in a clinical trial to make the choice of whether or not to stay.” Right now, “if you get pregnant, you’re out. Boom, that’s it,” she says. “But they were already exposed to the risk, and now they’re not getting the benefit. And so we don’t think that’s actually ethical.”

Thalidomide was prescribed to pregnant women to treat morning sickness, without ever having been tested in pregnant women. “We took the wrong lesson from thalidomide,” Lyerly says. “The first lesson of thalidomide is that we should do research, not that we shouldn’t.”