Astronomers have uncovered evidence of a rotating disc of material circling a massive young star in a nearby galaxy for the first time.

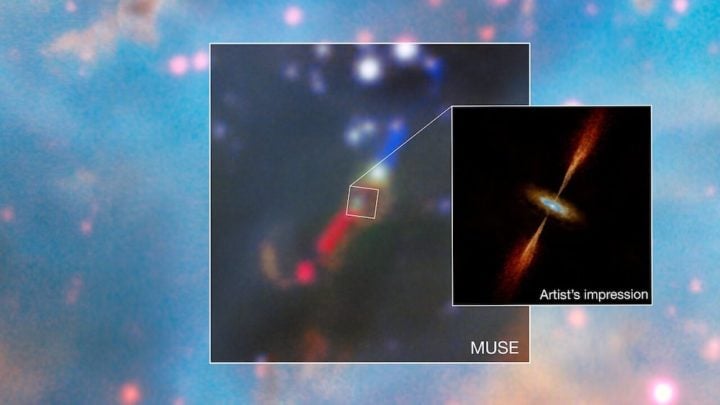

This mosaic shows, at its center, a real image of the young star system HH 1177, in the Large Magellanic Cloud, a galaxy neighboring the Milky Way. The image was obtained with the Multi Unit Spectroscopic Explorer on ESO’s Very Large Telescope and shows jets being launched from the star. Researchers then used the Atacama Large Millimeter/submillimeter Array, in which ESO is a partner, to find evidence for a disc surrounding the young star. An artist’s impression of the system, showcasing both the jets and the disc, is shown on the right panel.

(ESO/A. McLeod et al./M. Kornmesser)

Megan Reiter, assistant professor of physics and astronomy at Rice University, was part of the team of researchers who announced their discovery in a study published in Nature.

“This is strong evidence that high-mass stars, which are several times bigger than the Sun, form in the same way as lower-mass stars,” Reiter said. “That’s been a big question for a long time.”

Located in a galaxy neighboring the Milky Way called the Large Magellanic Cloud, the disc-sporting star was first discovered thanks to a protostellar jet ⎯ a signature feature of forming stars.

“As a star forms, the cloud of surrounding matter collapses, forming a disc,” Reiter said.

Megan Reiter is an assistant professor of physics and astronomy at Rice University. Image credit: Brandon Martin/Rice University

“The disc feeds material onto the star, which will throw away about 1-10% of it into these big bipolar jets. These jets can be quite large, so they’re easy to spot. Because they are shot out as part of this accretion process, the jets are also a bit of a history record that can tell you something about how the star is putting itself together.”

The jet was first spotted using the Multi Unit Spectroscopic Explorer instrument on the European Southern Observatory’s Very Large Telescope.

“After we saw the jet, the natural next thing to say is, well, these jets have to come from a disc ⎯ there must be a disc around that star,” Reiter said.

To test this hypothesis, the team used the Atacama Large Millimeter/submillimeter Array (ALMA) in Chile to collect data on the fledgling star and its surroundings.

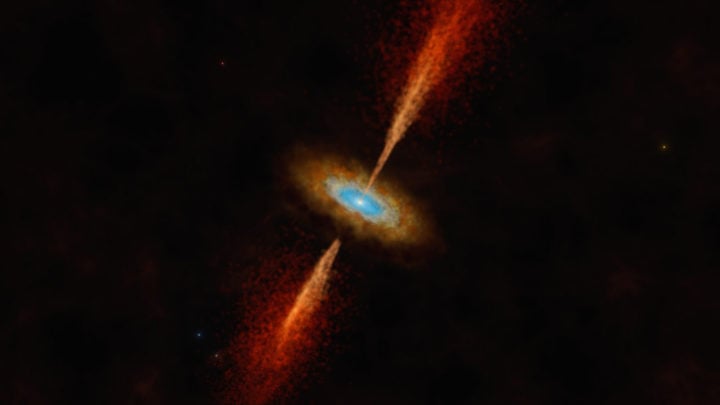

This artist’s impression shows the HH 1177 system, located in the Large Magellanic Cloud, a neighboring galaxy of our own. The young and massive stellar object glowing in the center collects matter from a dusty disc while expelling matter in powerful jets. Using the Atacama Large Millimeter/submillimeter Array, in which ESO is a partner, a team of astronomers found evidence for this disc’s presence by observing its rotation. This is the first time a disc around a young star — identical to those forming planets in our own galaxy — has been discovered in another galaxy. Image credit: ESO/M. Kornmesser

“Trying to spot a disk around a high-mass star is challenging, not least because it’s a relatively short-lived phenomenon,” Reiter said, explaining that a low-mass star like the Sun ⎯ with an approximate lifespan of 10 billion years ⎯ would only sport a disc for 3-10 million years during its formation.

Moreover, at least in the Milky Way, the stardust swirling around high-mass stars tends to shroud their surroundings from view, making it difficult to observe a disc taking shape. Thankfully, visibility is much better in the Large Magellanic Cloud, where star-forming matter is different.

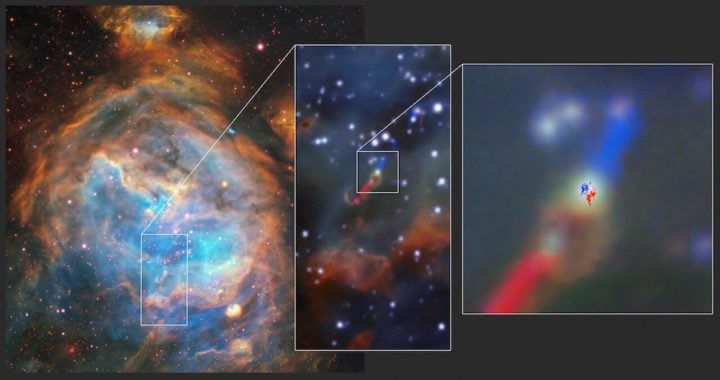

With the combined capabilities of ESO’s Very Large Telescope (VLT) and the Atacama Large Millimeter/submillimeter Array (ALMA), in which ESO is a partner, a disc around a young massive star in another galaxy has been observed. Observations from the Multi Unit Spectroscopic Explorer on the VLT, left, show the parent cloud LHA 120-N 180B in which this system, dubbed HH 1177, was first observed. The image at the center shows the jets that accompany it. The top part of the jet is aimed slightly towards us and thus blueshifted; the bottom one is receding from us and thus redshifted. Observations from ALMA, right, then revealed the rotating disc around the star, similarly with sides moving towards and away from us. [ESO/ALMA (ESO/NAOJ/NRAO)/A. McLeod et al.]

“It’s arguably more exciting to discover a disc in this neighboring galaxy as opposed to our own, because the conditions there are closer to what we think things were like earlier in the universe,” Reiter said. “It’s like we’re getting a window into how stars formed earlier on in the evolution of the universe.”

Anna McLeod, an associate professor at Durham University in the U.K. and lead author of the study, said that upon seeing evidence for a rotating structure in the ALMA data, she and her team could scarcely believe they had detected the first extragalactic accretion disc.

This dazzling region of newly forming stars in the Large Magellanic Cloud (LMC) was captured by the Multi Unit Spectroscopic Explorer instrument (MUSE) on ESO’s Very Large Telescope. The relatively small amount of dust in the LMC and MUSE’s acute vision allowed intricate details of the region to be picked out in visible light. (ESO, A McLeod et al.)

“It was a special moment,” McLeod said. “We know discs are vital to forming stars and planets in our galaxy, and here for the first time we’re seeing direct evidence for this in another galaxy.”

Source: Rice University