From Africa to Southeast Asia, the Trump administration is cancelling US support for projects designed to replace coal, oil and gas with clean energy, pushing instead for the use of American taxpayers’ money to support planet-heating fossil fuels.

Since Donald Trump took office in January, he has scrapped energy transition partnerships with South Africa, Indonesia and Vietnam and is trying to halt US backing for the African Development Bank (AfDB) and multilateral Climate Investment Funds.

At the same time, his administration has ordered the US Export-Import Bank (EXIM) to start supporting coal power projects abroad and, seemingly with some success, is putting pressure on the World Bank to fund more fossil fuels.

Climate campaigners said these changes would foster dependence on coal, oil and gas in developing countries, worsening climate change and holding back economic development.

At energy security talks, US pushes gas and derides renewables

US cuts to South Africa’s JETP

Since 2021, a group of wealthy countries including the US have teamed up with the coal-reliant emerging economies of South Africa, Indonesia and Vietnam on Just Energy Transition Partnership (JETP) plans to swap coal for clean energy in a way that is fair to workers and communities.

But Trump’s administration has pulled out of these deals. In March, the rest of the rich nations involved issued a statement saying the US’s withdrawal from the South African partnership was “regrettable”.

It meant the US would no longer provide $56 million in grants, and the US International Development Finance Corporation (DFC) would not provide $1 billion in loans on commercial terms or equity investment to South African projects. Even projects already being implemented were cancelled, according to a South African foreign ministry spokesperson.

Coal-reliant South African provinces falling behind on just transition

Projects funded by other countries in the coal-reliant province of Mpumalanga include developing green hydrogen, energy-efficient homes, better electricity transmission and mapping areas suitable for wind turbines.Coal-reliant South African provinces falling behind on just transition

US contributions represented just under 10% of the total grants provided and a similar share of the total pledges. The other countries said they remain “fully committed” to the programme and “some partners are exploring possibilities for supporting work previously being carried out by the US”.

CIF coal transition programme on hold

As well as ending direct support, the US is also throwing a spanner in the works of $500 million due to be provided by the CIF, which works through multilateral development banks, and its Accelerating Coal Transition (ACT) programme for South Africa.

In 2022, South Africa asked the CIF for $450 million in loans and $50 million in grants under this programme to repurpose three aging coal-fired power plants in Mpumalanga, replace the electricity they generated with renewables, fund community projects in the province and make its buildings more energy-efficient.

The plan – approved that year by governments on the CIF committee that oversees this programme, including the US – was for this money to unlock around $2.1 billion more, mainly from development banks and the private sector.

But in July 2024, following elections and a change of environment minister in Pretoria, South Africa tried to change the investment plan to reflect state-owned utility Eskom’s decision to keep the three coal plants running – albeit below their full capacity – until 2030.

With the nation having suffered frequent planned blackouts due to a shortage of electricity supply, the government cited “energy security concerns” for the proposed change. Altering the plan meant it had to seek approval from this committee – the Clean Technology Fund’s Trust Fund – again.

By the time of the committee meeting in February 2025, with Trump now in the White House, the plan had still not been signed off by governments. The co-chair’s meeting summary shows that South Africa urged governments to give it the greenlight.

But in early March, the US prevented those funds from being approved, according to a Bloomberg news report. Two sources with knowledge of the discussions also told Climate Home that the US was holding back funding.

While the US under Trump has become hostile to phasing out fossil fuels in general, it has a particularly bad relationship with South Africa’s government, cancelling all “aid and assistance” in February due to Pretoria’s criticism of US ally Israel and US allegations of discrimination against South Africa’s white minority.

First carbon credit scheme for early coal plant closures unveiled

The CIF committee next meets on June 11 in Washington, where the updated South African energy investment plan is due to be discussed, according to Bloomberg. A CIF spokesperson told Climate Home the agenda is “currently being finalised” and that deliberations related to the South African investment plan are “ongoing and not public”.

“A delay in funding means a delay in decarbonising the South African power sector,” said Tracy Ledger, head of just transition at the Johannesburg-based Public Affairs Research Institute.

Trump budget cuts to harm development

In the proposed US budget for 2026 – which has to be negotiated with Congress – the White House has proposed cutting $275 million of spending allocated to the CIF and the Global Environment Facility together, as well as taking $555 million away from the AfDB’s fund for Africa’s least developed countries because it is “not currently aligned to Administration priorities”.

Samuel Maimbo, a World Bank vice president who is bidding to lead the AfDB, said US cuts to the African Development Fund would have a “huge impact on Africa’s development”.

Even as it seeks to take money away from clean energy, the Trump administration has said it is willing to spend more public money supporting fossil fuel projects abroad – and has pressured international lenders like the World Bank to do the same, with some success.

EXIM backs coal projects

On the day he was inaugurated, Trump issued an executive order announcing he would withdraw from the Paris climate agreement and “revoked and rescinded immediately” former President Joe Biden’s international climate finance plan. He instructed the EXIM president at the time, Reta Jo Lewis, to report back in 30 days on how she had complied with this order.

On May 1, the board of directors of the bank – which provides loans and other support to US businesses to help them export their products – voted unanimously to reverse a ban on funding coal-fired power projects.

Solar squeeze: US tariffs threaten panel production and jobs in Thailand

According to Kate DeAngelis, deputy director of economic policy at Friends of the Earth US, who monitored the meeting online, the board’s acting chair James Cruse told those present that this move put EXIM in line with Trump’s executive order and that Cruse had supported it all along.

A bank spokesperson told Climate Home that the entire board agreed that these changes “put the Bank in alignment with charter and administration priorities”.

Asked whether, as DeAngelis claimed, the bank was quicker to heed Trump’s order to fund coal than Biden’s previous order to phase out support for fossil fuels, the spokesperson said that “as an independent agency, EXIM always works to align with the priorities of the current administration”, adding that it “is most wholly focused on ensuring [our] mission and charter mandates are upheld”.

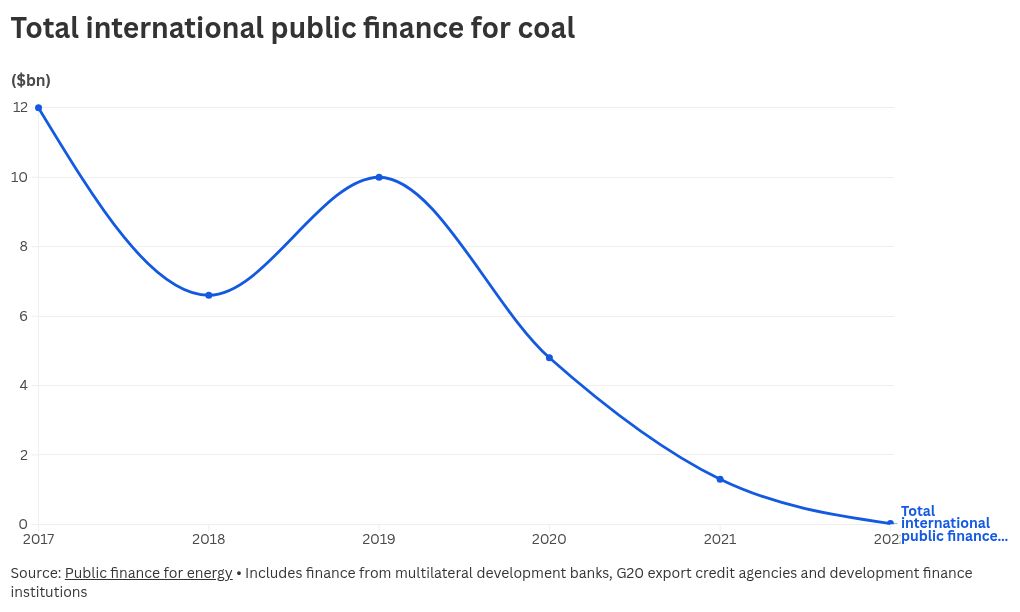

Funding foreign coal makes the US an outlier internationally. In recent years, almost all major nations – including China – have promised to stop funding coal-fired power plants abroad, although some exceptions persist.

Oil Change International campaigner Laurie van der Burg said public funding was crucial for coal plant developers as these projects are now deemed too risky by private banks. She added that EXIM’s move was “concerning” but unlikely to reverse the global trend of coal finance dropping.

Push for World Bank to back gas

In April, meanwhile, US Treasury Secretary Scott Bessent said that the World Bank – which provides cheap loans and grants to developing countries – “must be tech neutral and prioritise affordability in energy investment”. “In most cases, this means investing in gas and other fossil fuel-based energy production,” he said.

Shortly before Bessent’s speech, World Bank President Ajay Banga told reporters he would seek approval from the bank’s board to enable more gas projects, which are currently only supported in limited circumstances. Customarily, the head of the World Bank is effectively chosen by the US president, with Bessent saying in April that Banga needed to earn the Trump administration’s trust.

Trump’s first 100 days: US walks away from global climate action

Fran Witt, who attended the bank’s spring meetings as part of her work with the NGO Recourse, told Climate Home that the bank should spend taxpayers’ money on playing “a leadership role in helping [energy] transition rather than fostering dependence on gas”.

She said that, while the World Bank top leadership will push hard for gas, it would be a “pretty thorny discussion”, with “more progressive executive directors probably trying to hold fire”.

Voting power is proportionate to the shares each government holds and, while the US has the most at 16%, other nations like Japan, China and European countries also have substantial sway.

If the bank does start backing gas infrastructure like pipelines and ports, Witt said she expects a lot of developing countries will be keen to access that funding – particularly in Asia where “there’s a massive dash for gas”.